Cars, trucks, motorbikes, bicycles all share the road. Simon Vincett explores the benefits of separating motor vehicle and bicycle traffic.

As cycling networks extend throughout Australian cities, a host of new riders are poised to take up active transport. Louise Treloar, 25, of Sydney, started riding to work this year.

“It’s been a good option for me—it’s really cut my time to get to the station,” Louise explains. “I ride from my home in Bellevue Hill to the station at Bondi Junction. It would usually take me 20 minutes to walk but on my bike it only takes five minutes.”

“When it gets a bit warmer I want to ride all the way to work. It would take about 40 minutes but it would avoid me having to catch the train. They are just building a proper bike lane which would be on my way, so it will be really handy when that’s done. If I don’t have to take the train I’ll save a lot of money and then I’ll get my exercise done for the day as well.”

On her current commute Louise uses an on-road bike lane and a shared path. Her route all the way to work, when complete, will also offer off-road sections including through parkland, as well as on-road bike lanes. She is one of many who will be encouraged to ride (and maintain or improve her health while doing it) because infrastructure which separates her from the traffic is in place.

Experts say that separating bike routes from motor vehicle traffic is key to encouraging people to take up riding as a mode of transport. From the example of Copenhagen, where between 1995 and 2005 bicycle trips increased by 30% and bicycle-related crashes reduced by half, Australian cities have drawn inspiration to develop cycling-specific road facilities in an attempt to achieve a similar growth in people riding bikes.

These cycle-specific road facilities include what are sometimes called in Australia ‘Copenhagen lanes’: bicycle-only traffic lanes that are separated from motor vehicle traffic by a physical barrier of some sort. These are also separate from pedestrian footpaths. This degree of separation is considered the gold standard for facilitating bike riding for the broad range of people who can ride bikes for transport, which includes children and senior citizens.

“Separation is all a matter of degrees,” explains Bicycle Network’s Senior Policy Advisor Garry Brennan.

“A small amount—say a standard bike lane—will get you some additional riders, but greater separation—a physically separated lane—will get you a great many more riders, and, critically, they will be different riders, the riders we need on the road to make cycling an everyday event for every person,” Brennan says.

“The real magic of good separated infrastructure is that it completely changes the composition of the riding community, introducing a wide cross-section of society—the people that always have had a desire to ride a bike, but feared the threat of traffic.”

This starts with encouraging more women to ride, because they aren’t currently braving Australian roads in sufficient numbers.

“Anywhere in the world where we have great, separated infrastructure, women are more than 50 per cent of the riding population, but in Australia we get nowhere near that, even in Melbourne we struggle to get above 25 per cent,” Brennan points out.

“But once you put some distance between the bikes and the cars, that figure changes rapidly: you go from 25 to 35 per cent as has happened with the eastern end of La Trobe Street in Melbourne, or up to 45 per cent in Swanston Street.”

Australia’s first ‘Copenhagen lanes’ opened on Melbourne’s Swanston Street in April 2007 and cost $550,000 to construct. Bicycle Network praised the Victorian government for their vision in upgrading the existing ‘economy’ on-road bike lanes which had limited appeal for the wider commuting public.

Melbourne now has two more major stretches of separated bike lanes serving the CBD: Albert Street connecting the inner east and La Trobe Street providing a cross-city route in the north of the CBD. In addition, there are shorter sections on Cecil Street in South Melbourne, connecting an off-road path to the South Melbourne Market, and on St Kilda Road where this major arterial connects to the CBD at the bottleneck of Princes Bridge. All of these separated lanes collect from and distribute to on-road lanes to complete the through-journey of the rider and make a viable network of routes to traverse the city.

A focus on network building has been notable in the approach of the City of Sydney, under the direction of Lord Mayor Clover Moore. The City website declares it is working hard to “fully interconnect the City’s villages with a high-quality cycleway network that is within a five minute bicycle ride from all residents”. This is in line with the municipal target to “increase the number of bicycle trips between 2 and 20km made in the City of Sydney, as a percentage of total trips to 20% by 2016”. It is realising its ‘cycleways’ by combining on-road lanes, off-road shared paths and separated bike lanes according to the type of facility that can be applied in different streetscapes.

Garry Brennan agrees this pragmatic approach is the best path forward. “It makes sense to prioritise these designs for where you know you have popular destinations that can generate large numbers of trips: central cities, universities, hospitals—anywhere where there are large employment attractors with residential communities within 15km.

“This is where you will see the most benefit for the cost outlay. Retro-fitting separated infrastructure comes at a cost, but it is by far the least costly way of increasing capacity on a road. For example it could cost $20 million for separation on a long major route into a CBD, but to add the same capacity by train, tram or bus would cost hundreds of millions, so there are tremendous savings for the taxpayer.”

Brisbane is another Australian metropolis seeking to encourage and accommodate bike riders as a larger proportion of commuting traffic. As in Melbourne, this comes with the backing of the state government, which has produced the Queensland Cycling Strategy that sets a target of doubling cycling for transport by 2021.

In January 2014 the Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads led the charge in Australia for facilitating more people cycling by producing a guideline for design and construction of separated bike lanes. The Separated Cycleways guideline takes up the focus of the Queensland Cycling Strategy, explaining that to achieve the target: “road design must focus on the comfortable daily transport of new bicycle riders, especially women, as well as current bicycle riders.” This document comes prior to any guideline prepared by the national body Austroads, which is the usual arbiter of Australian road-design standards.

“It is noteworthy that Australia started building separated lanes before there were any standard engineering guidelines,” Garry Brennan observes. “It was such an important advance that we just could not wait. Queensland has led the way with its guidelines, and a national standard is now urgently required to give practitioners the confidence to get on with the job.”

Queensland has led the way with its guidelines, and a national standard is now urgently required to give practitioners the confidence to get on with the job.

Bicycle Queensland CEO Ben Wilson says the document has put separation on the agenda in the northern state.

“Before this guideline existed separation was not part of the Queensland agenda but something from the south or a freaky overseas model. Now we’ve got a true-blue Queenslander version, which is well done, and will provide engineers in towns in the north of Queensland and the west of Queensland—people a long way from head office—with a reference to deliver a safe cycleway system in existing roads and new roads in their regions.”

Of course, installing separated bike lanes, with their wider footprint than an on-road bike lane, is not without its challenges—a major one being its impact on existing car parking.

“We have a narrow road reserve—12m rather than 14m in Melbourne, for instance,” Wilson explains, “and separation can only come at the expense of car parking. That can be intolerable in some circumstances.”

While it can be a downside, the upside according to Garry Brennan is that separated lanes move bike riders away from parked cars and car doors that can open into a rider’s path.

“Not only do riders experience a greater degree of security with separation, but the risks of doorings are greatly reduced. In fact, mid-block crashes come down significantly, and will drop further as pedestrians slowly adapt to the presence of bikes in those lanes,” Brennan says.

Ben Wilson is convinced separation is the necessary condition to make the next population of cycle commuters start up their regular riding. While in the 1970s advocates including John Forester (in the USA) believed ‘vehicular cycling’ was the answer—where riders share the road and behave assertively to mix with motor vehicles.

However, there’s now a new school of thought emerging

A more recent study in Portland, USA, by Roger Geller, found that people fall into four categories in terms of their willingness to ride for transport: ‘the strong and the fearless’, ‘the enthusiastic and confident’, ‘the interested but concerned’ and ‘no way no how’.

John Forester’s model, it seems, appeals to ‘the strong and the fearless’, which according to Geller’s study comprises less than 1% of the population.

Ben Wilson says the evidence is proving Geller’s research.

“The evidence is proving that separation is what’s getting people on bikes,” he says.

“The benefit is for new riders, less confident riders, female riders, families and kids. There’s a great movement of 20-somethings riding bikes in the city. It’s the cool, the chic—they’ve got no desire to wear lycra but they’ve got a big desire to be on a bike. That’s a powerful force for normalising cycling and getting it into new demographics.”

“We’ve had good discussions with Transport and Main Roads and Brisbane City about doing some innovative separation techniques,” Wilson says. “There are low-hanging fruits where, for one reason or another, there is the space.

“In new developments there are opportunities to get it right in the planning stage. Queensland is a rapidly expanding state, so in growth corridors, such as Caloundra South not too far north of Brisbane where they’re talking about a 50,000-person community being developed, there’s an opportunity to have world-class bike facilities built from day one.”

Examples of separated bike lanes from other Australian cities show varying degrees of popularity and usefulness for local bike riders.

Adelaide, under Lord Mayor Stephen Yarwood, has recently become enthusiastic about bikes as transport. The city hosted the international Velo-city conference in May this year and as a showcase opened the first length of separated bike lane in the city. Called the Frome Street bikeway, this route traverses the CBD from south to north, with a planned extension to North Adelaide. The City Council website declares it is “working hard to create a city where people of all levels of cycling ability feel that they can cycle safely, and to make cycling the most convenient form of transport for local trips.” The opening of Frome Street Bikeway was celebrated with a mass ride attracting hundreds of participants.

Tasmanian bicycle advocates have pushed hard for a separated lane for Hobart’s popular Sandy Bay Road and also Collins Street to join the Hobart Rivulet Track to the CBD, but the political will isn’t yet there to make it happen. Instead Sandy Bay Road was given on-road lanes with minimal removal of car parking and Collins Street awaits a bike-friendly treatment.

Perth has a few sections of off-road path that have recently achieved notoriety for being used on occasion by car drivers attempting to avoid traffic jams.

Adelaide’s Velo-city was also where Bicycle Network launched its latest campaign asking the Federal Government to commit $7.5billion to build separated bike lanes and paths. The campaign aims to get more people on to bikes by building the infrastructure which encourages riding.

The ‘Please, Tony’ campaign asks Australians to send a letter to Prime Minister Tony Abbott asking for the funding because:

Inactivity creates a public health burden of $13.8billion per year.

59% of Australians want to ride a bike but they’re concerned about cars and trucks.

Separated lanes and path will overcome that concern.

If 59% of Australians take up riding the saving is $8.1billion per year.

$7.5billion will buy 7,500km of separated bike lanes and paths and would transform Australia into the most bike-friendly and physically active country in the world.

Bicycle Network wants the Federal Government to see the value of building such infrastructure for the health and wellbeing of Australians.

Garry Brennan says ultimately, the usefulness of separated lanes and other bike facilities is proven by their connectedness.

“It’s still early days for separation in Australia and many of the new routes are not completely connected up yet, but when we get to having fully hooked up, end-to-end separated routes on the high volume corridors into our central cities, we will see unprecedented growth in bike commuting.”

Ride On content is editorially independent, but is supported financially by members of Bicycle Network. If you enjoy our articles and want to support the future publication of high-quality content, please consider helping out by becoming a member.

The development of urban bicycle riding in Australia is being hampered by the high risk of serious injury faced by bicycle riders. Recently road trauma figures have risen steeply and this is ascribed to the increasing popularity of cycling.

The risk of serious injury or death faced by a person using a modern form of transport such as train, tram, plane or even motor car has dropped to such a low value that a mishap is no longer anticipated. But the reverse is the case for cycling, where the risk of collision is very high, and the level of risk is at a third world standard.

At present there is inadequate collection of reliable data on the frequency of serious injuries to cyclists per million kilometres travelled.

This needs to be rectified if the person in the street is to be convinced that bicycle riding is a safe alternative form of transport.

No doubt this will lead to the adoption of many more fully separated paths.

I am a 68 year old cyclist who has been riding a bike off and on most of my life. I have been riding about 1,400kms per year for the past 4-5 years in Sydney. 4 weeks ago on a quiet cul de sac that I have ridden hundreds of times as I was cautiously approaching a tight bend that I know is potentially dangerous a red P plater came in the opposite direction on my side of the road. With limited room to take evasive action I had to brake strongly to avoid a head on collision and went over the handlebars. It broke my neck (C1 and C2) and dissected an artery leading to my brain. I was incredibly lucky avoiding death and quadreplgia by millimetres. The artery is blocked by a large clot and so far a piece has not broken off leading to a stroke. I have a 5-6 month rehab period in front of me. I hope to be able ride my bike again. I cannot stress enough the importance of separating bikes and cars.

Hi John, thanks for sharing your story. As a new bike commuter, your experience is what I fear. I hope you continue your recovery and that you reach your goal of getting back on your bike.

I only learnt to ride a couple of years ago and as a middle-aged female cyclist I agree with many of the descriptions in the article of how new/female cyclists feel. I relax and enjoy my commute into town a lot more when I am on the separated bike paths.

A separated bike lane is not the BE ALL END ALL.

Why?

Because there is an inherrent nature in our culture of not being considerate.

I’ve found in my experience that separated bike lanes means being completely out of the mind of pedestrians and cars. And this is much worse than being a noticed obstacle to navigate around.

Melbournes “fancy” city bike lanes are a joke. I find the few times I’ve ridden them that I’ve had to pull up short from pedestrians coming in and out of cars and crossing the bike lane to get to the pavement. Separated bike lanes that merge with car lanes at intersections and cause issues of who goes first, with cars often edging hard up against the curb to turn left cutting off cyclists.

St Kilda has a joke of a bike path where bikes go both ways on one side of the road, so drives assuming they only have to look right (as they should) for on coming traffic/bikes can often almost take out a cyclist. Not to take away that to see around cars parked past the bike lane they have to edge out onto the bike path completely.

The bike lanes that intersect over super tram stops on Swanston walk also completely ill thought out as to this day pedestrians still stand all over them.

Dedicated bike paths that run along car lanes are what is consider the best approach to developing a safe bike culture, where bike thoroughfares on roads are needed.

It’s the equivelant to having pedestrians not walk on bike paths down near the yarra. It’s a shared path, and so cyclists and pedestrians need to find a way to use it together and BE CONSIDERATE.

Cars give more consideration to pedestrians than cyclists, even when they jaywalk, but curse and frown at cyclists. Why?

Is giving drivers more reason to feel cyclists have less of a right to use roads beneficial to cyclists being safer on any road? My opinion is it doesn’t.

I’ve noticed some road racer type cyclists don’t like the idea of separated cycling infrastructure because they feel drivers will get annoyed at them for choosing the road instead of the separated path. On the road these racer cyclists get to ride fast and keep pace with the cars where as on the separated paths they have to be more courteous and ride slower. This is the conundrum we face here in Australia… we have racer type cyclists advocating their point of view while we are trying to promote cycling as a everyday activity that anyone can do in normal clothes and on casual commuter bikes that are more suited to separated infrastructure….. super sad really.

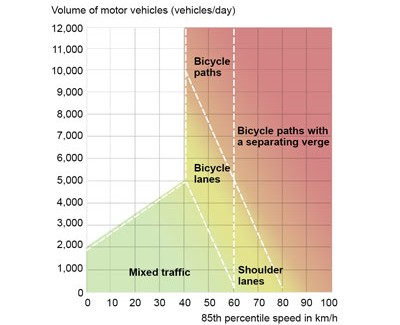

You include a graph about speed limits and suggested measures but what about the issue of speed limits? While pushing for separated facilities, why no mention of the importance of reducing speed limits within the urban area (eg so a majority of roads are 30km/h – that battle with VicRoads deserves to be fought)?

I am a 49 year old daily commuter of 9 years in Sydney. I moved from the Northern Beaches to the Inner West so that I could cycle to work. I now have greatly improved fitness , am not sitting for 45 mins in traffic and my ride home has become essential to ” switching off. ” from work. I just got taken out by another bike rider who mistook the pedestrian crossing , (stupidly placed at the intersection of a T crossing ,at the end of a bike lane) for a continuation of that bike lane. I went over the handlebars, landing on my head and then amazingly rolled on my left side, breaking my left arm. My neck and spine are amazingly fine. I had right of way across the T and I was doing about 30k. So lucky.

Please don’t reference Swanson St bike lanes as being a success story. They are the most ridiculously designed lanes on Melbourne. Whose idea was it to have a bike lane that goes straight through a tram stop?!

They should dedicate a couple of roads to cyclists and peds and get serious about getting cars out of the CBD.

I don’t think the bike lane goes through the tram stop, but you do have to be careful near the pedestrian crossings that get tram passengers to and from the tram stop.

If we could get some sort of dedicated bike lane through the South Wharf/South Gate area that would be absolutely awesome and probably reduce the injury accident toll substantially. No idea why this has not been addressed. Oh wait, it costs money, doh!

I am a 66 year old cyclist, ex racing cyclist (Road & Track) who has commuted to work up to 20Kms to the CBD’s of Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide every working day of my life, rain, hall, or snow! My biggest fear of injury is of a driver opening his door as I am about to pass. There is little that one can do to avoid injury in these situations except be very vigulant.

However if bike paths were built close to the left hand side of car doors where kids and others will open a car door without looking, serious accidents are certain to occur. There must be adequate spacing between the bike lane and the car door.

I was disappointed that Brisbane’s ‘bike lanes’ were given such a rap. There is a lot of talk about how encouraging the state government is towards bike riders, but in reality there is little done. There are, admitedly, excellent ‘bike path’s in and around the suburbs which provide limited options for commuters but excellent places for casual cycling. However ‘Bike lanes’ in and around Brisbane city consist of green marks on the road that just disappear unexpectedly when it all becomes too hard. If there really is this Master Plan and International Design – then let’s see it! Cycling in Brisbane city itself is too dangerous for me – there are virtually no marked cycle lanes and the car drivers don’t indicate, don’t look and basically don’t care – probably much as it is in your city. I am 59, have experienced several broken bones, including my back, commute a 40 km round trip daily – and I wouldn’t ride in the city if you paid me. This current governemnt is all talk in a number of areas as they struggle for re-election, bicycles and cycling is just another platform they think will earn them votes, even though their delivery is non-existent. Please don’t give them credit where there is none due.

I find the separated lane in Swanson street highly problematic. The bike lane is separated from the main road by concrete bars. As you ride south into the city the road slopes down, so if you were to come off your bike, particularly if crunched your face or head, the result could be catastrophic . And this is not an unlikely scenario because the bike lane is quite narrow – in fact I think the chances of hurting yourself on the concrete bars would be high and I take extra care just there.