Nat Earl launches into cycle touring with a comprehensive exploration of exotic Myanmar.

In 2015 there are not many places in that have retained the aura that Myanmar has. Dotted with temples, one of the largest networks of rivers in the world, a mountain range almost as long as the Great Dividing Range but three times as tall and a mix of cultures, it makes an ideal destination for bike touring.

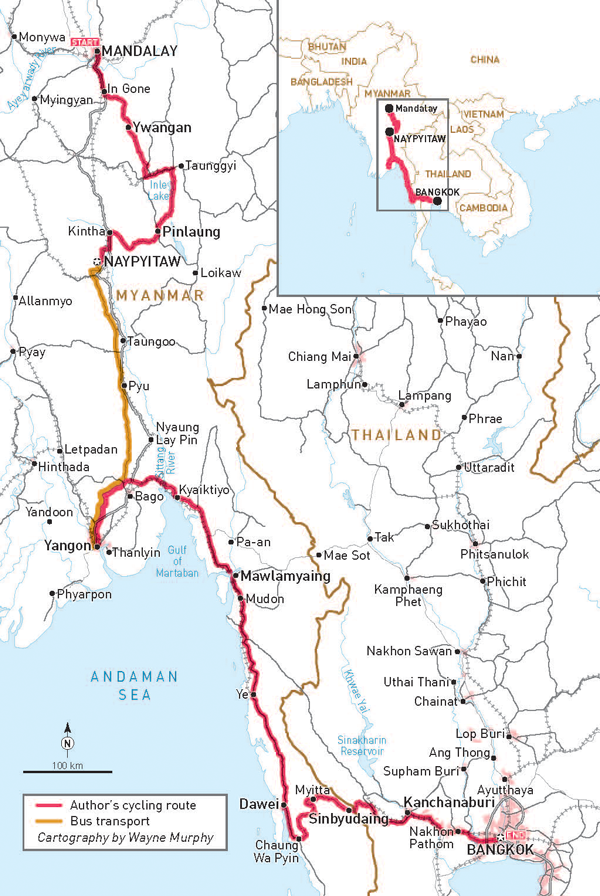

Being a first time cycle tourist I was initially nervous setting off from Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city. I was to travel roughly 2000km to Bangkok over four weeks through the Shan state, onto the capital Naypyitaw, and continue to Yangon and then to the southern coastal city of Dawei. While Myanmar has become more open to tourists in recent years, I was to ride in some areas that were not very well travelled and as a result didn’t know what to expect. Only in the past decade has the country been moving towards opening its borders to trade, tourists and modernisation.

Within half an hour of arriving in Mandalay I was in the deep end. My bike (which I had brought with me) was stranded on the tarmac in plain sight for almost an hour, the result of the shambolic airport organisation. While there was a long queue to thoroughly search and x-ray all arrivals, the guards simply waved me through without a second glance gesturing my box wouldn’t fit. Deciding to change money in the airport, I handed over 200 crisp US dollars (the Burmese will only accept unfolded, unwrinkled, post-2006 notes) and I was handed back a fistful of 200 notes equivalent to a dollar each.

Soon enough I was in a taxi headed to the heart of Mandalay, getting my first glance at the roads I would spend the next four weeks on. Although the road we were on had two lanes in either direction, it seemed most of the traffic either travelled in the centre of the road or three abreast. The driver’s liberal use of his horn for the entire hour-long trip made me wish I had brought a louder bell.

After a few days getting my bearings and exploring Mandalay I was headed for the hills of the infamous Shan state, an area that has endured civil war with the military government since WWII and until recently accounted for a large portion of global opium growth. The 60km on the main national highway saw some hair raising moments (thankfully some of the only on the trip) and total chaos because of road construction (which unfortunately became a trend). But pulling off the highway and into the hills saw the road become a little quieter.

Two more trends emerged quite quickly. First was the absolutely stunning scenery—endless untouched jungle dipping into valleys punctuated by slow flowing rivers and hilltops capped with pagodas. The reward for the endless climbing (1600 metres in 40km) was greater and greater views that could be seen. The second theme was the curiosity and kindness of the local people. A 6’5”, white guy in colourful lycra on a bicycle isn’t exactly a common sight in remote Myanmar but the responses of the locals were always hilarious. From unapologetic staring, to enthusiastic waving or—my personal favourite—the screams of children who I imagine were saying “Mum, look at this weirdo riding a bike!”

There are many ways to explore Myanmar by bike. Self-guided trips are easy and popular despite language and cultural barriers, but many tour options exist as well. Most good guide books will list a variety of reputable services. It’s possible to buy or rent decent bikes in Yangon and Mandalay; finding modern bikes elsewhere can be a challenge.

Three of the most popular short trips around Myanmar include:

– By far the most popular journey includes renting a bike from Mandalay and riding down the Ayeyarwady River to the iconic temple city of Bagan before either riding or catching a ferry back down the river. The round trip can be completed in less than a week.

– Leaving from Yangon riding north-west through the villages scattered on the Ayeyarwady Delta towards Pyay and catching a bus or riding back to Yangon.

– Or for the slightly more ambitious: Riding through Bago, to The Golden Rock and onto the seaside town of Mawlamyine gives a good mix of traditional culture and colonial history. There are bus services back to Yangon or onward to the Thai border. For a scenic journey, expect to be travelling for two weeks.

In a place where many people don’t even earn a thousand dollars a year, I was touched by the kindness I received. Offers of water and food from shopkeepers insisting on not taking any money were commonplace. Tucking a sneaky 500 kyat (50 cents) somewhere on the way out was an easy way to show some gratitude.

Myanmar is the third last country in the world to allow Coca Cola (only North Korea and Cuba remain as holdouts). For a country coming to grips with how to deal with the outside world, there are still teething problems, especially for those travelling in more remote areas. Foreigners are strictly not allowed to camp. I was told a story by two Hungarian cyclists who were woken up in the middle of the night in a rubber plantation and frog marched to the nearest town and this put me off attempting it. On top of that, hotels and guest houses that host foreigners must hold a special licence. While this usually wasn’t an issue—I typically found a guest house every 80–100km—it was occasionally difficult to manage.

Myanmar is a collision point for many cyclists. There were a number of inspirational (or crazy) people I met along the road on awe-inspiring journeys. Ian was a Scotsman traveling solo through South East Asia; he was the first cyclist I met and helped me through the few days I was feeling off colour. Ian had a very successful blog about dogs and spent most of our days photographing the many hundreds we met on the road. A Spanish couple of professional rock climbers had started in Vietnam and had been riding for six months with climbing, cooking, camping and photography equipment totalling 50kg each. A trio of Germans who were nine months into a year-long journey from Berlin to Shanghai had spent a month travelling through India and Pakistan without an escort. Alex and John were a pair of Canadians I spent four days riding with. Alex was 67 years old and absolutely flogged me on the bike. John courageously rode a sweltering 100km day after consuming just about an entire town’s whiskey supply and disappearing in the middle of the night.

Leaving the popular tourist destination of Inle Lake I chose to ride south west towards Naypyitaw through an area I was unsure had connecting roads or a hotel. The first day turned into a tough 90km ride with 2000m of elevation gain, and ended with me eventually finding a bed in a small town hotel that had never had a western guest (though many Chinese businessmen). During a fried chicken noodle dinner with a 60 cent Myanmar lager at the local beer station I struck up conversation with a local health official who spoke good English. He warned me the next day’s ride to Naypyitaw would see me crossing two sets of mountain ranges with no hotels along the way. But you could ride it in two hours on a motorbike (Burmese have no concept of distance in miles, only by time on a motorbike—this proved to be troublesome more than once).

“Riding along a twenty lane road with not a single other person or vehicle in sight will remain one of the strangest experiences I have ever had.”

Not knowing what to expect, I set off early. After an hour of climbing I plunged into a winding 35 minute descent to rival the Swiss Alps for grade and, amazingly, road quality. Giggling at the bottom I was blissfully unaware that ahead of me lay 2500 metres of vertical gain to scale over the next 160km. I arrived in Naypyitaw at 9pm that night, unfortunately discovering myself on the wrong side of the sprawling city from the hotel district. I enlisted the help of a very drunk government official who zigzagged his motorbike through the bizarre streets of Naypyitaw while I chased. He led me to a hotel that had the frontage of a Las Vegas casino, but without a single person staying the night. Despite this, the non-negotiable rate of 100 US dollars per night had to be paid—I was too tired to care.

Naypyitaw is a capital that was built from the ground up in 2006 at an estimated cost of $5 billion dollars. The Lonely Planet guide describes it as “a mix of Brasilia and Canberra with a peculiar Orwellian twist”. This could not be closer to the truth. The city is 50km from north to south and officially houses 1.5 million people (though in truth probably has closer to 100,000). Twenty-lane roads with roundabouts the size of whole city blocks link the city in a disorganised way. Almost the entire population is employed by the government. A “quick” hour long ride around parliament house will see the moat surrounding it and the small military battalion tasked with constantly guarding it.

I elected to catch a bus the 400km to Yangon (formerly Rangoon) to save some days of boring highway riding and allow a short stop for slightly better quality food and R&R in the quickly developing city. A lively metropolis of 5 million, Yangon has all the makings of a thriving Asian economy. Great food, bustling markets, and suicidal taxi drivers (though motorcycles are banned). It is one of the few places in Myanmar where foreign investment and tourism has had a distinct effect on the day-to-day function of the city.

After a few days in Yangon the urge to continue cycling was too great to ignore. A few days of riding saw me arrive in Kinpun, the base town for Kyaiktiyo Pagoda (or the Golden Rock), an important buddhist site with a rock on the edge of a cliff. Crammed into the back of a small truck with fifty pilgrims, it was a hair-raising forty-minute drive up the hill. I was glad to get out, especially when I saw the tires were as bald as a monk’s head.

With two Canadians I met at the Golden Rock, we planned to travel south to a city called Dawei—a small port town at roughly the same longitude as Bangkok. Armed with nothing but a broadsheet map, we planned a route along what appeared to be a major road. Leaving Mawlamyaing (a sleepy port town that inspired stories from George Orwell and Rudyard Kipling) we followed the road south but it quickly turned bad. Burma’s roads are almost exclusively hand-built by very poorly paid workers who scatter rocks crushed by the roadside from wicker baskets. There seems to be no organisation to construction with great lengths of road torn up to be resurfaced over a period of months or years.

Thinking things couldn’t get worse, the road began to climb and eventually evolved into a fully functional quarry. We battled 25km of challenging uphill riding through fine silt and large corrugations. At the top of the hill we hit a checkpoint for Thanintharyi state. Passports were taken and discussion was had. We agreed with the policeman to stay at a designated hotel in a town 80km down the road. I was pulled over twice over the next 80km by policemen ensuring that we were “safe”. We met our final escort, who led us through a maze of country roads to a small hotel. He kept insisting we were in “grave danger” and again must follow a predesignated route the following day—about two hours by motorbike, he assured us (where have I heard that before?).

My two Canadian friends set off earlier than me the next morning. I followed half an hour later and immediately got a puncture. After two the previous day and three earlier in the trip I was using multiple patches on tubes in a size I knew I wouldn’t be able to find in Burma. The road was made of stones embedded into the ground, with some the size of rockmelons and very sharp. I struggled with two more punctures on my cyclocross bike. While the weather had been ideal most of the trip, that day was well above 30° with high humidity. It was very tough going. Soon enough I heard the sound of crashing waves and crested a difficult hill to be greeted by a 3km stretch of beach that was to be the road—with not another soul except myself and the two Canadians. The previous 60km washed away.

I farewelled my Canadian friends in Dawei—they were headed back to Yangon—and I prepared myself for the final leg of the journey: the border crossing to Kanchanaburi in Thailand. Having ridden on gravel roads for the previous four days I knew what to expect. The lack of hotels meant a 140km gravel slog to the border. I had met a few cyclists who had attempted to cross in the opposite direction and had met border guards who forced them to take a shared taxi instead. I was determined to push through.

At the 40km mark there was a checkpoint with a dozen soldiers. They warned of a dangerous road ahead and one of them made a phone call. Another Canadian, this time in a car, appeared. He was local to the area and said there was still civil war tension and that was why cyclists have been struggling to get through. Surprisingly, the sergeant returned my passport and wished me well.

Sure enough, I got a flat within 1km. The road followed a white water river curving through a mountain range. Where previously it had been easy to find a stall selling water every few kilometres, here they spaced out to over 30km. Occasionally an overloaded car carrying cargo from Thailand passed, but there was very little traffic. Worryingly, I passed more guys riding motorbikes carrying what looked like WWII era rifles. Strangely they all seemed happy to see a foreign cyclist and waved enthusiastically as they passed. A long 140km passed and I finally reached the border checkpoint. I spent my last Kyat on some proper ice cream—a luxury I missed in Myanmar. I was glad to be able to get some quality food and the next few kilometres to the Thai side of the border were on butter-smooth tarmac—bliss. But no amount of green chicken curry and machine-built road could take the unique experience of Myanmar from my mind.

While a solid working bicycle will suffice for almost any trip, as a tragic bike nerd I took a lot of enjoyment from building the “perfect” bike for this trip. It was based around a versatile Soma Doublecross—one of the few XXL steel frames that don’t cost a kidney—and built up using a mixed Shimano groupset of Ultegra road and XT mountain parts, utilising bar end shifters for durability and simplicity. Drop handlebars provided multiple hand positions and a familiar feel. A slight oddity was the choice of a Cane Creek Thudbuster, an elastomer seat post that takes the buzz out of 150km-long gravel roads. Ortlieb classic pannier bags gave complete waterproof luggage carrying, while Inside Line Equipment provided a front bag that doubled as a reasonable daily shoulder bag. While I learnt a few things about bike set-up on the trip, the bike provided a great base from which to explore this beautiful country.

PHOTOGRAPHY NAT EARL

Ride On content is editorially independent, but is supported financially by members of Bicycle Network. If you enjoy our articles and want to support the future publication of high-quality content, please consider helping out by becoming a member.

Hey Nat

Love the write up.

We’ll also be cycling through next march via the Indian border towards Thailand.

when you say post 2006 US notes do you mean 2006 and up, or 2007 and up.

We have many 2006 USD notes in mint condition we want to use.

What do you think?

Have you got a list of towns with guest houses you stayed at?

Many thanks

Fred.

Hey Fred,

Post 2006 was suggested by a guidebook (I think Lonely Planet). Both government and storekeepers have relaxed on the perfectly crisp notes over the past couple of years from what I’ve been told. So long as your money is clean and not totally crinkled or old, I imagine you should be fine. You’ll see they don’t treat the local currency with much respect anyway.

Towns I stayed at:

Mandalay

Kyaukse

Ywangan

Kalaw

Nyaungshwe

Pinlaung

Naypyitaw

Yangon

Bago

Kyaikto

Kin Pun

Thaton

Mawlamyine

Setse Beach

Ye

Kanbauk

Dawei

I didn’t book a single guest house on the tour (during Jan and Feb) and only had trouble one night when I arrived in Yangon at midnight. Although there are the restrictions on foreigners, people are very friendly and accommodating and most towns with a population larger than a few thousand will have a place you can stay.

Enjoy your trip! It’s a wonderful country.