Limiting global warming and defining sustainable development have both been recently negotiated at the global level. Simon Vincett asks Australia’s leaders how bike riding can play a role in our national commitments.

In November 2015, the Paris Conference on Climate Change reached, for the first time since the inaugural Conference of Parties (COP) in 1995, a legally binding and universal agreement on climate, with the aim of keeping global warming below 2°C.

“The Paris Agreement also sends a powerful signal to the many thousands of cities, regions, businesses and citizens across the world already committed to climate action that their vision of a low-carbon, resilient future is now the chosen course for humanity this century,” stated Ms Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the body that convenes the conference.

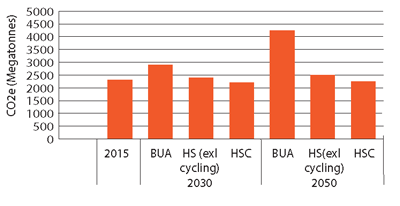

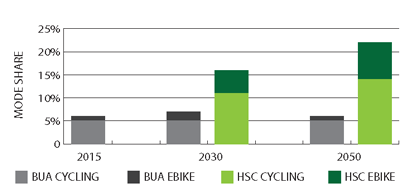

At the same time, a new study by the Institute for Transport Studies at University of California, Davis—also released in November 2015—quantified how much increased bike riding delivers in reductions of CO2 emissions and energy use of transport, while also reducing the overall cost burden of transport. Called A Global High Shift Cycling Scenario, the study modelled the effect of a shift in usage of bikes and ebikes to become 22% of all transport trips in all cities worldwide by 2050.

With this shift, the model found that CO2 emissions and energy use would be 47% reduced by 2050, and cost is reduced by a staggering US$128 trillion. This is compared to continuing in a ‘business as usual’ manner where the private motor vehicle with an internal-combustion engine makes 80% of trips.

These sorts of results should attract the attention of policy-makers in Australia, whose task following the Paris Agreement, is to draft ‘Nationally Determined Agreements’ that will halt and begin to decrease emissions causing global warming. These must include actions on transport, which globally accounts for nearly 25% of all carbon emissions. Transport’s contribution in Australia is a lesser 16–17%, but not because we are doing anything right to curb it—our vehicle emission standards are some of the worst in the developed world—but because our coal-fired electricity generators are the dirtiest in the world and our agriculture is heavily reliant on fossil-fuel-derived fertilisers.

Also urging all nations to action on global warming—and focussing all development on a sustainable and socially responsible trajectory—are the UN Sustainable Development Goals. These new goals, established in September 2015 and guiding development for the next 15 years, follow on from the Millenium Development Goals of 2000–2015. Whereas the Millenium Development Goals were guidance for developing countries though, this latest round of goals—which have been agreed through the UN general assembly process—provide all countries with guidelines and responsibilities to make all development sustainable and globally just.

Goal 13 on the list, for instance, is to “Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts”. The UN expressed optimism about this, saying: “The pace of change is quickening as more people are turning to renewable energy and a range of other measures that will reduce emissions and increase adaptation efforts.”

In order to combat climate change, Goal 7 exhorts countries and businesses to: “increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix”. The target set is: “By 2030, enhance international cooperation to facilitate access to clean energy research and technology, including renewable energy, energy efficiency and advanced and cleaner fossil-fuel technology, and promote investment in energy infrastructure and clean energy technology”.

So how is the Australian government conducting the country in order to meet our international climate commitments?

Senator Janet Rice, Spokesperson on Transport for The Greens and a former Senior Strategic Transport Planner in local government, told Ride On: “There’s a big gap between those guidelines and what governments are willing to sign up to as motherhood statements, and then to be serious about the implementation of it.”

Senator Janet Rice, Spokesperson on Transport for The Greens and a former Senior Strategic Transport Planner in local government, told Ride On: “There’s a big gap between those guidelines and what governments are willing to sign up to as motherhood statements, and then to be serious about the implementation of it.”

“Our current government has a woeful track record when it comes to complying with international agreements,” she points out. “That’s the challenge for us Greens to be pointing out that we are not operating consistently with the things we are signing up to. The community and society need to be calling our governments out on that as well. Regular reviews [stipulated by the Paris Agreement] is one of the good things that has come out of the targets, so that we can keep track every five years of how we are going.”

Labor’s Mark Butler said: “As the Shadow Minister for Environment, Climate Change and Water, sustainability is a critical aspect of all the work I do. One of my core priorities is determining how best to reduce carbon pollution. Part of Labor’s ten point plan for better cities is investing in active transport solutions which connect up with public transport in order to help encourage people to take up low carbon travel option. Making bikes a viable option for commuters is a key opportunity to help reduce carbon pollution, reach our emissions reduction targets and provide positive health impacts.”

The Minister for the Environment, the Liberal party’s Greg Hunt is keeping a tight focus on cities. “Improving the productivity, liveability and accessibility of Australia’s cities is a national priority for the Turnbull Government,” he said. “Ensuring access to a choice of transport modes, including cycling and public transport, can play an important part in delivering these objectives.”

An area of focus for the current Abbott–Turnbull government has been air quality. Minister Hunt in December 2015 released a National Clean Air Agreement struck between the federal government and the Australian states. The Environment Minister told Ride On: “The National Clean Air Agreement’s initial work plan includes reducing air pollution from non-road petrol engines such as garden equipment and marine engines, along with wood heaters. These sources can contribute up to 10 per cent of air pollutants in cities. The Agreement also includes a priority setting process to help governments to deliver coordinated and practical responses to air quality problems.”

Senator Rice is not convinced, describing the National Clean Air Agreement as “tinkering around the edges”.

“Cars overall are much, much more of an impact on our air quality than marine engines and wood burners,” she says. “But they are accepted as the baseline: ‘We couldn’t possibly be doing much to change that’. You’re not going to get to zero emissions until we get to a fleet of electric cars fuelled on 100% renewably produced electricity and that’s a long way off.”

The High Shift Cycling study, however, envisages a world where transport is much more diverse—and finds tremendous benefits in that diversity. Its underlying assumptions are that trips less than 10km are cycle-able and more than half of all trips are cycle-able by that definition. Across all global cities, the model anticipates a change from the current average of 7% of trips made by bicycle and ebike to 18% of trips in 2030 and 22% of trips by 2050.

The High Shift Cycling (HSC) study was preceded by a High Shift study of 2014, also conducted by the Institute for Transport Studies at University of California, Davis. The prior study modelled a shift to a greater proportion of public transport, cycling and walking but was criticised as not ambitious enough about the potential for increase in cycling as a mode share. The High Shift Cycling study was commissioned by the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), the European Cyclists’ Federation (ECF) and the Bicycle Products Suppliers Association (BPSA).

So how can such a shift come about, particularly in Australia, where cycling to work across our metropolitan cities currently accounts for about 2% of trips? The study explains: “The HSC scenario is predicated upon an aggressive policy agenda where tough political decisions are made at the national level and in cities around the world in favor of density, locational efficiency, mixed use, and parking management. Political leaders have strong incentives to choose this path, as it leads to a dramatic reduction in societal investments and operating and energy costs, and it provides improved economic well-being, enhanced social equity and stability, and strong reductions in environmental damage over the current trajectory.

“Since the HSC scenario saves money, paying for it is not problematic. Cities and countries across the spectrum of wealth have demonstrated the potential for rapid increases in cycling, and it is clear that such a scenario is entirely possible in the given time frame. However, a large amount of political will is required to change course from the BAU [Business as usual] to implement an HSC scenario, and it is not clear if cities and countries will be able to find such will, especially given the low capacity for long-term planning in many places.”

There are examples of where it has been done the study points out: “Over the long term, it may be possible for many cities to replicate the success of cycling in cities such as Groningen, Assen, and Amsterdam in the Netherlands, where cycling exceeds 40 percent of all trips, and in Copenhagen in Denmark, which grew from low levels of cycling after World War II to more than 45 percent of trips today.

“Seville, Spain, is particularly relevant, as it grew cycling mode share from 0.5 percent to nearly 7 percent of trips in six years (2006–2012), with the number of cycling trips increasing from five thousand to seventy-two thousand per day. Seville achieved this by installing a backbone network of nearly 130 kilometers of protected cycle lanes (cycle tracks) throughout the city and implementing a bike share program with 2,500 bicycles and 258 stations in a dense bike share network across the city. Paris, Buenos Aires, and Montreal have also experienced similarly rapid increases in cycling through investments in low-stress networks of cycling infrastructure and large-scale bike sharing schemes.”

Senator Janet Rice, a long-time advocate of bike riding, thinks we should be pushing more cycling to have a mode share in Australia even greater than the HSC overall average of 22 per cent. “My rule of thumb for what we should be aiming for in Australian cities is one third walking and cycling, one third public transport and one third private car use,” she says. “I believe that’s eminently achievable and would meet all our transport needs.

“If we did have a mix of one third walking and cycling, one third public transport powered by renewable energy and one third private vehicles powered by renewable energy we could get there. The critical thing to say is ‘This is where we’re heading for’ and set out the plan to do it and seriously implement it. It really means giving priority to walking cycling and public transport.”

Rice asserts that it is commitment to the status quo that is the issue and not cost. “We’ve got the government and the Labor party not doing anything, certainly in terms of stationary energy and in transport. Both are operating on the expectation that the status quo is here to stay. Any of the transport modelling is … pretty much presuming that the mode share is going to be 80% private car use.

“Public transport is so much more efficient. As a rule of thumb, it’s basically the same cost for a brand new rail line with stations as it is for a tollway, and you can just shift so many more people doing that. And then you get to walking and cycling: cycling is a thousand times cheaper per kilometre than a tollway project, and again it is much more efficient in terms of space in shifting people. Every dollar we put into facilities for walking and cycling represents so many dollars that we are saving on our transport costs.

Even at that cost saving, we’re not talking about bargain basement bike facilities in these calculations, says Rice. “That’s a cost of a million dollars per kilometre, which is quite expensive for a cycle path. It includes on average doing all those bridges and having completely separated off-road paths. It’s a million dollars per kilometre rather than a billion. The cost of the East–West tollway [abandoned by the Victorian Labor government in 2014] was $6.8 billion for six kilometres.”

Rice urges bold action from Australia’s political leaders to meet our international commitments to limit global warming. “We’ve got to have the vision and courage to prioritise bikes and walking and public transport, and actually to be saying ‘Our plan for the city is that we are going to be saying yes, we are prioritising affirmative action for cycling, walking and public transport’. We’ve had a failure of leadership to do that, to give people a really legitimate choice to get out of their cars.”

More biking more quickly

In the HSC scenario, the following policies, based on a number of best practice cycling policy recommendations, are used to quickly increase cycling levels:

- Cycling infrastructure is retrofitted onto existing streets and roads with relatively inexpensive materials to create backbone networks of low-stress bicycle routes on arterial streets, small residential streets, and even intercity roads;

- Construction includes one kilometre of cycling lanes (either pathways or striped lanes on city streets, along with street furniture and secure bike parking) for every 2.5 million cycling kilometres that occur each year;

- Implementation of bike share programs in large cities to connect to transit and provide initial impetus for cycling;

- Laws and enforcement practices are changed to better protect cyclists and walkers;

- Aggressive investment is also made in walking facilities and public transport to create a menu of transport options in cities that can be combined to accommodate a wide variety of trips without the need for motor vehicle use;

- Metropolitan land-use and transportation planning are coordinated so that new urban development investments are directed toward parts of the city where existing and planned cycling, walking, and public transit infrastructure can accommodate nearly all trips from that development without spurring additional motor vehicle use. New transportation investments are planned for areas where they can most effectively reduce existing motor vehicle use;

- Policies that had formerly supported additional motor vehicle use, such as minimum parking requirements, free parking on public streets, and fuel subsidies, are eliminated;

- Policies such as congestion pricing, VKT (Vehicle Kilometres Travelled) fees, and development impact fees are adopted to charge a price for driving that accounts for negative externalities. These fees fund investment in sustainable transport;

- Funding is increased for sustainable transport to allow for high and sustained investment in cycling, walking, and public transportation infrastructure and services;

- National policies support and spur city level change by providing funding for cities to invest in cycling and other active and public modes, and financing to help leverage existing revenue streams to spur large-scale investment;

- National governments adopt best practice standards from the best performing countries to ensure that the highest quality infrastructure is built;

- Global institutions, such as development banks, change lending practices to shift investment from roads toward cycling and other more sustainable modes.

Source A Global High Shift Cycling Scenario

Read what key federal politicians have previously told Ride On about what bike riding can offer to improve the amenity and competitiveness of Australia’s cities.

Ride On content is editorially independent, but is supported financially by members of Bicycle Network. If you enjoy our articles and want to support the future publication of high-quality content, please consider helping out by becoming a member.