Ro Privett recounts his epic adventure on Siberia’s Kolyma Highway through Far East Russia—otherwise known as the ‘Road of bones’.

“You will definitely meet bears,” remarked our drunken Russian guide. After a pause and a reflective look away, he followed up, in a concerned voice, “I hope you escape”. Needless to say, the three of us looked aghast at each other. We just hoped that for Anton, in whom we’d placed all our trust, that it was simply ‘the vodka talking’. Time will tell. With that stark thought uppermost in our minds, we each skolled one last shot of vodka, shouting ‘peidodnya’—that is ‘drinking to the bottom’—to induce good karma in the proper Russian fashion.

Up until that moment we were never really sure whether we would come face-to-face with the Russian brown bears. Some say you won’t see them and they are no problem. Others say it’s a big concern. Now, as we were about to embark on our remote Siberian expedition, the locals confided their concerns to us. For the first time, we know the risk is real. In the morning, our merry band of five Aussies—nicknamed the ‘Kolyma Komrades’—will also get real on our 1,570km mountain bike journey through this Siberian taiga wilderness, whether the bears like it or not.

Like many trips, this journey was a long-held dream of an adventurous mind. This dream belonged to my father, Leigh, who visited the Kolyma region in the early nineties on an ultra-marathon challenge when it was first opened up to visitors. He became enchanted with the landscape and the history of Siberia and Far East Russia. The seed was planted. Now, almost 20 years later to the day, he had returned to fulfil this desire for more, with us comrades in tow.

Like many trips, this journey was a long-held dream of an adventurous mind. This dream belonged to my father, Leigh, who visited the Kolyma region in the early nineties on an ultra-marathon challenge when it was first opened up to visitors. He became enchanted with the landscape and the history of Siberia and Far East Russia. The seed was planted. Now, almost 20 years later to the day, he had returned to fulfil this desire for more, with us comrades in tow.

My father is as tough as old nails, even at the ripe old age of 67, and so is Hugh, dad’s neighbour and the other elder of our group. Then there are the ‘pups’: Jase, a meteorologist with a heart of gold who takes a shine to anything outdoors; Dan, an Outdoor Education teacher, small business owner, irrepressible source of goodness and the anchor man of many adventurous trips; and me, who we can simply describe as a wilderness seeker.

The next morning we found ourselves posing for the obligatory pre-trip photos, albeit with one or two of us nursing sore heads. Our moment had arrived. We were about to start our ride east out of this small, mostly derelict town of Khandyga. Yesterday we had driven from the metropolis Yakutsk in Anton’s UAZ (a kombi van on steroids) across the great Lena and Aldan rivers, notably with one breakdown already, though nothing that some Russian ingenuity couldn’t handle.

Yesterday, Anton seemed a little puzzled and unsure of our journey and today we curiously found ourselves unsure about him. It appears that some Russians can’t handle their vodka. Go figure—especially as the name extends from the Russian word ‘voda’ meaning ‘water’, which is supposedly how freely they drink it. As we excitedly started our wheels in motion, Anton was well and truly seized up in bed. He muttered to us he would catch us up later in the day. He never got around to giving us the ‘bear safety talk’ as promised. Things never seem to go to plan in Russia.

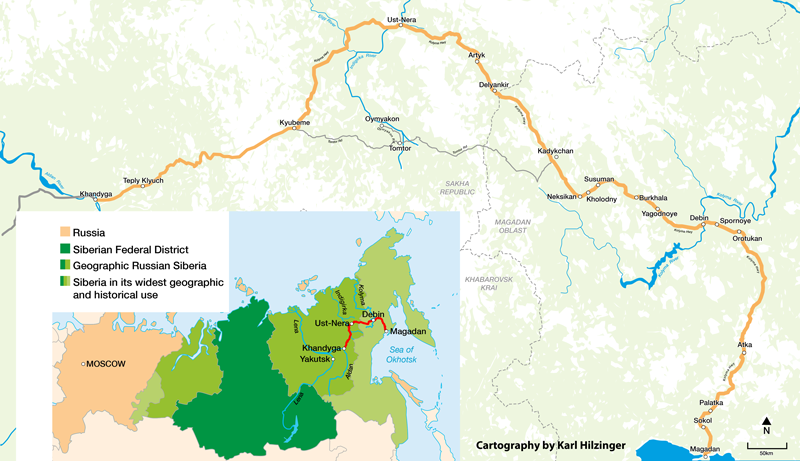

As we pushed out the first few kilometres trying to wear our backsides in, we found one of the first quiet moments to reflect upon this adventure of ours. As much as it was a journey to discover ourselves, it was also a journey to discover and learn about this historic Kolyma Highway, which extends from Yakutsk to Magadan in Far East Russia. Back in the 1930s, 40s and 50s this road had a very tragic story. Millions of prisoners were forced to build this road during the reign of Joseph Stalin to access the inland gold and treasures. From minus 60 degrees Celsius to 40 degrees above, the prisoners worked fifteen hour days. The camps, known as Gulags, were abysmal, with virtually no sanitary facilities and repressive discipline that has made the name synonymous with inhuman cruelty. It is said that over a million prisoners died during the construction of this highway and they were simply buried under the road because it was too hard to dig through the surrounding permafrost. It thereby became the largest cemetery in the world and was nicknamed the ‘Road of bones’.

With some good miles under our belt, we feared one of our greatest concerns may have already come true. That is, that our trusty Russian guide may not be so trusty after all. It was well after lunch time and as yet, we had still not seen Anton. It was mid-afternoon before Anton appeared, swearing never again to go near Russia’s poison water. Not only is he carrying all our camping gear and food (all the vodka is now finished) but he is supposed to track us down during the day—hopefully a bit earlier—to supply back up on the road. By and large, we will ride by ourselves, covering roughly 70–120km a day on our faithful mountain bikes.

The days in the saddle become a mixed bag of various road conditions, deserted and dilapidated old mining towns, and the occasional reminder of the prison camps. In years gone past, the raw remnants of these camps were clearly evident but these days it’s much harder to glimpse them as the forest and new road construction conceal the past. Most noticeable are the gravestones commemorating the many car accidents and ‘frozen to death’ break-down fatalities. The cocktail of freezing conditions, remoteness and a poor excuse for a road has proven quite lethal. The highway has recently received government funding, however, so a new road is being built over the existing road for more reliable access to the region.

The days in the saddle become a mixed bag of various road conditions, deserted and dilapidated old mining towns, and the occasional reminder of the prison camps. In years gone past, the raw remnants of these camps were clearly evident but these days it’s much harder to glimpse them as the forest and new road construction conceal the past. Most noticeable are the gravestones commemorating the many car accidents and ‘frozen to death’ break-down fatalities. The cocktail of freezing conditions, remoteness and a poor excuse for a road has proven quite lethal. The highway has recently received government funding, however, so a new road is being built over the existing road for more reliable access to the region.

As we approached a remote outpost called Kyubeme and neared the mountains, the weather was beginning to turn and we all sensed that we were now entering the cold heart of this taiga wilderness. In two sections the modern-day highway diverts away from the alignment of the old road before re-joining. Kyubeme marks the beginning of the first diversion. The old road is said to be near impassable, as it is no longer maintained. Large four-wheel-drive trucks struggle through occasionally, suggesting some truth in the adage that Russians don’t tend to build better roads but instead build bigger trucks. We had hoped to venture this way seeking a true glimpse of the Gulag era but, upon warnings of treacherous river crossings, sanity prevailed.

Along this section of old road is a no-name turnoff to a little place called Oymyakon that is well and truly frozen into the record books. It is the coldest inhabited locality on earth, excluding the poles. Sitting in a narrow valley by the Indigirka River, the mercury has plummeted to an astonishing 71 degrees below zero during the long dark winter, which is hard to fathom for us Aussies. Later on, as we sit around the campfire sipping on hot Milos, that chilling thought of Oymyakon returns as we gaze across to an iceberg still commanding its place in the river.

Wearing two sets of clothes is often necessary in this neck of the woods. Not only does it help stave off the cold but it also offers some relief from the dreaded mosquitoes. At times during the year, they can reach plague proportions and they are known to pass on disease such as encephalitis. We rigged up a huge mosquito net under our tarp to keep them at bay but thankfully our timing for the journey was spot on, as the mozzies were reasonably dormant.

Back in the saddle, we were now under fire from a cold front bringing consistent rain. Thankfully the mercury hadn’’t dropped below zero yet. We arrived at the mountains, and on one of the first passes we were hailed by some truck drivers keen to share their adoration of vodka. Though we have already experienced this Russian pastime, saying no would be culturally insensitive.

Back in the saddle, we were now under fire from a cold front bringing consistent rain. Thankfully the mercury hadn’’t dropped below zero yet. We arrived at the mountains, and on one of the first passes we were hailed by some truck drivers keen to share their adoration of vodka. Though we have already experienced this Russian pastime, saying no would be culturally insensitive.

As we rode over the mountains, the fog and mist were well and truly set in, adding a surreal character to what we were doing. We were constantly pinching ourselves. The road gradually transformed into mud—much to our bikes’ disgust—so it was a relief to reach our campsite before dusk. Most campsites were nothing more than a makeshift roadside affair in the local forest, but hot food and banter were daily highlights. A constant source of laughter was the toileting routine, or as we were instructed to call it, ‘govno’. Anton made a strong argument for always making a lot of noise when nature calls, so to scare off any bears. Needless to say, this gave a bunch of Aussies plenty of ammunition to take it to the next step and reel off any verbal diarrhoea that we could. You’ve got to love the simple life, and the simple pleasures that go along with it.

Speaking of bears, they were never too far from our minds or conversations. When something is higher on the food chain than you and you’re on its turf, it provides a constant eeriness. Anton finally gave us the ‘bear talk’ as promised but it seemed quite casual and token, not to mention many days late. They say there aren’t a lot of bears in this region, but also that a few people a year are taken and killed by them in Siberia. We are also told that locals feed them by the roadside (in order to hunt them) so they are reasonably prone to hang around by the road. Anton declares that he is not willing to sleep under the stars for fear of his safety and chooses to sleep in his car, where the food is kept. Obviously we can’t all sleep in the car, so we expendable comrades are forced to sleep outside. Somewhat reassuring is that Anton has provided us with large firecrackers to use as bear deterrents should one visit during the night. We never quite got our head around that procedure though. We sleep in hope.

Our next goal was an outpost called Ust Nera, a thriving mining town in the middle of nowhere. The heavens well and truly opened up and the road turned into a quagmire. We were simply caked in mud from head to toe—unrecognisable to each other. Jase was the first one to have his gear cables chock up with mud but he deftly switched to kicking his derailleur into gear. That was until his bike shoe refused to release from his pedal. Jase shared our laughter, knowing that we soon would be in the same predicament.

When we eventually reached the stark grey town, so used to heavy industry and foul weather, we weren’t allowed inside our accommodation due to our filthy state. However, Dad pulled off a masterstroke and found some hot showers in the local hot water station. In Siberia, hot water is at a premium so they allocate a large station for such a cause. The showers were far from hygienic but it was still one of the best showers that we have ever had.

Then came the peak cultural exchange of the trip. We were thoughtful enough to have packed some Aussie souvenirs including the faithful boomerang. The staff at the hot water station took to it and it was out to the muddy car park to test this stick out. Not only were there the usual weird and wonderful throws and associated laughter, but the piece de resistance when one chap hurled a big throw that well and truly came back. Realising it was headed for the tin shed, everyone was up in arms before the inevitable ‘bang’ that almost knocked over the shed. Like kids in the school playground, our grins and playful delight transcended the language barrier and we were left with a moment that we will never forget. With a hearty farewell we left the boomerang with those guys.

Then came the peak cultural exchange of the trip. We were thoughtful enough to have packed some Aussie souvenirs including the faithful boomerang. The staff at the hot water station took to it and it was out to the muddy car park to test this stick out. Not only were there the usual weird and wonderful throws and associated laughter, but the piece de resistance when one chap hurled a big throw that well and truly came back. Realising it was headed for the tin shed, everyone was up in arms before the inevitable ‘bang’ that almost knocked over the shed. Like kids in the school playground, our grins and playful delight transcended the language barrier and we were left with a moment that we will never forget. With a hearty farewell we left the boomerang with those guys.

Ust Nera is one of those places that you can proudly claim that ‘you’ve been there’. It’s not particularly attractive to say the least but it’s definitely on the ‘road not taken’. The episode at the hot water plant has become emblematic for me of our experience of the locals we encountered. Most presented a cold and hard exterior but once you got to know them, they have a spirit of collectivism, where other people are comrades and community is the key to survival. It was very heartening.

The long hours on the bike prompted us to compose a riding song;

‘Aussies in Siberia,

Imagine the hysteria

Pain in the posterior

Aussies in Siberia.’

The journey now took on a strong sense of grey and not just because of the rainy weather. We took a small side-turn off the highway to meander through a town called Kadykchan, which resonates a grey nature in many regards. Known as the city of broken dreams, this old coal mining town was built by the Gulag prisoners roughly 80 years ago. In its heyday, it was home to 11,000 people, all heavily involved with coal production. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, this place like many others lost its funding and the work quickly dried up. Everyone simply packed their bags and left—the place abandoned with all its infrastructure intact. Photos remain on walls and kids’ toys lie idle in front yards. There was no noise but at the same time it wasn’t quiet—there were voices and noise palpably absent in the silence. Like many evocative locations on this trip, this is one place we will never forget.

With that haunting experience behind us, we rolled into Susuman, which is as close as we can get to an oasis in this unforgiving landscape. Our bodies were well and truly aching, so this town provided a well-earned break, a rest and reprieve from the mud and rainy weather. After we scrubbed up, we relished the novelty of a small café, where a few ‘peidodnya’ rounds of pivo (beer) were enjoyed.

From Susuman the old road diverts from the modern highway for the second time. It’s a road that we desire to travel. Early feedback was promising but then Mother Nature dealt us and Siberia a blow. Severe flooding had resulted in landslides along this road, making it impassable. Even the main road is rumoured to be shut in places ahead. One wonders if these two old-road sections will ever be travelled again if the effects of Siberian weather continue unopposed. With the thought that much of the physical reminder of the Gulag era may soon be lost, we were glad that we were there, upholding the memory in our small way.

With the forecast looking as grim as the road conditions, we improvised mud guards with our best Bear Grylls skills. The roadside litter was just the ticket, though there was brisk competition for the best milk bottles, vodka cans and rubber mats. It was a bitterly cold morning. We had a sense that this was a sign of things to come. The heavens opened up and not only were we dealing with the moisture from above—it seemed the passing cars and trucks gave little concern to our plight and threw in extra mud baths for good effect. Riding became an exercise in keeping warm.

The following morning dawned to reveal a snow blanket over the landscape and our campsite. This was the Siberia that we came to see. The only way to get warm was to start riding—after we de-iced the bikes. We couldn’t believe we were riding at minus four degrees! Again we reflected on those Gulag prison camps.

We found a small store in the backstreets of a largely deserted old town which revived us with some hot coffee. We set in for what should have been another hard and mostly uneventful afternoon. How wrong we were. Hugh and I were riding at the front of the group when a car approaching us in the distance was beeping their horn and driving erratically. It was at that moment that we saw it. A Russian brown bear was running off into the distance.

As much as we were sort of prepared for it, we instantly felt that we weren’t. With a shift in fortune, that bear could be running after us. Hugh and I waited for the fellow comrades to arrive. Once the approaching car had reached us and told us that the bear had disappeared up the hill, we slowly started riding again, hoping that safety in numbers would be our saviour. Dan noticed the bear’s footprint in the roadside mud. It was big. Very big. It was certainly a reality check, and was a prominent theme of discussions that night.

On the far side of another one-horse town called Debin we finally reached our namesake river, the Kolyma. The bridge stretching out ahead was simply enormous. You couldn’t help but be humbled in the presence of this mighty river. Rising in the Kolyma mountains, it is the seventh longest in Russia, flowing over 2,000 kilometres to the sea. It is frozen to depths of several metres for about 250 days each year, becoming free of ice only in early June, until October. This is just one of approximately 100,000 rivers in Russia, which together account for the second largest supply of fresh water in the world (Brazil is believed to be the largest, with the Amazon River).

Such an awe-inspiring sight deserves proper appreciation, so we pulled up stumps for the day. After a questionable cow’s liver stew, the night’s entertainment involved some tent dilemmas. The Kolyma was clearly in an angry mood, and overnight it rose several metres. Jase moved his tent well and truly uphill the first time but dad awoke to find himself almost swimming on two occasions. While funny, it was a close call, though at least it gave us a reprieve from his snoring!

Such an awe-inspiring sight deserves proper appreciation, so we pulled up stumps for the day. After a questionable cow’s liver stew, the night’s entertainment involved some tent dilemmas. The Kolyma was clearly in an angry mood, and overnight it rose several metres. Jase moved his tent well and truly uphill the first time but dad awoke to find himself almost swimming on two occasions. While funny, it was a close call, though at least it gave us a reprieve from his snoring!

We were now on a long stretch away from any outposts—just the way we like it. It felt like a road to nowhere: five Aussies and a Russian guide in the wilds of Siberia. The road was still pretty muddy and full of holes, so it kept us on our game. We’d become pretty hardened to mechanical issues. We found that if we gave dad’s rear wheel a firm knock on the spindle with a tomahawk it revived the drive system for a few more hours of riding. As we had also just heard about bears in the vicinity, carrying a tomahawk seemed a good idea on many fronts.

I remembered an inspiring talk by the intrepid adventurer John Muir that included a tale of a frightening encounter with a polar bear while trekking to the North Pole with Eric Philips. As the bear bolted towards them, he resorted to some previous advice and stood on his gear and made monstrous noises accompanied with a wild dance. It worked for Muir and Philips, so I decided the ‘bus stop’ would be my ‘get out of jail’ card. Hopefully the boys would follow suit.

Back in tight formation again, our man Anton drove ahead in hope of warding off the beasts. As you could well imagine, we had interesting discussions about what position in the riding order was safer during a bear attack. Any encounter we imagined would be randomly provoked, akin to a shark attack, so most theories went out the window, but it kept us simple men entertained nevertheless.

Into the midst of our bear fixation, some locals nearly ran us over in their sheer excitement to see us out in the middle of nowhere. They jumped out of their large American pickup truck and were all over us with the exuberance of paparazzi. It was quite infectious—another significant cultural moment when a meaningful connection transcended the limitations of the spoken language. They, like so many here, had a huge sense of camaraderie. Whenever we now encountered a Russian with the somewhat stereotypical cold and hard exterior, we looked deeper for the compassionate comrade inside.

It was another long stretch to the next outpost called Palatka. The daily kilometres were reasonably routine by now. The weather seemed to be warming as we neared the coast. Also changing was our level of isolation. We met another bike rider, a Scottish fellow, riding solo the other way. Loaded up with all his gear, he was clearly excited for the journey ahead—just like us only a few weeks back. Like kindred spirits we spoke with warm rapport, concluding finally with a cordial exchange of best wishes.

It was another long stretch to the next outpost called Palatka. The daily kilometres were reasonably routine by now. The weather seemed to be warming as we neared the coast. Also changing was our level of isolation. We met another bike rider, a Scottish fellow, riding solo the other way. Loaded up with all his gear, he was clearly excited for the journey ahead—just like us only a few weeks back. Like kindred spirits we spoke with warm rapport, concluding finally with a cordial exchange of best wishes.

We rode a few kilometres out of Palatka looking for somewhere to lay our heads. This night would be our last one camping out, and besides a small celebration it should have been a regular affair. But it was not to be. Unless Anton was taking the mickey out of us, he was definitely afraid of bears in light of many sightings around town. Our trusty guide even faced the car ready for a quick getaway down the road, leaving us pondering if any mad escape would involve us tent-bound folk. Maybe we were the decoy? There was not much we could do besides the usual precautions, so we laughed it off as best we could. The image remains with me of Hugh sleeping under the tarp clutching a firecracker for dear life. Now, where did I hide that lighter?

It was a restless night to say the least, with the subconscious mind playing its silly games, but by and large the bike riding fatigue won over. We figured dad’s snoring would scare off the bears anyway. Back on the tarmac, and before we could even find any morning rhythm on our treadlies, we were stopped in our tracks. A bear just ran off the right hand side of the road. Cripes—we were within a couple kilometres of camp. Not only was that a bit chilling, but it turned out that we were camping quite near the local tip, which the bears treat like a drive-through McDonald’s. In hindsight, all we can do is learn from it and have a chuckle, relieved that we still grace this earth.

With the taiga wilderness sadly behind us, we rolled up to the threshold of Sokol, the local airport town from which we would fly south in a couple days. There were smiles all around as we realised that we were about to pull this trip off. Also a hot shower would soon be making us look respectable. That night was grand. We dined out with local Russians, who inducted us into their town with a vodka and arm wrestling party. We flew the Aussie flag well, in regard to the arm wrestling that is. There’s something priceless about kindred strangers coming together from different cultures. A proud and passionate exchange of customs intermixed with comedic attempts at the others’ perplexing language. A few samples of alcohol seem to provide common ground, arguably enhancing the interaction.

With the night’s memories replaying, it was onto the tarmac for one last time as we pushed out the last seventy kilometres or so to Magadan. Dan was on the money when he said, “This will be by far the most dangerous day of the trip”, as many cars and trucks raced past us. The potholes were still keeping us on our toes, as we took on a more sleek riding formation, Tour de Siberia style.

With the night’s memories replaying, it was onto the tarmac for one last time as we pushed out the last seventy kilometres or so to Magadan. Dan was on the money when he said, “This will be by far the most dangerous day of the trip”, as many cars and trucks raced past us. The potholes were still keeping us on our toes, as we took on a more sleek riding formation, Tour de Siberia style.

It seemed that word had got around about us unusual Aussies, as the local TV station tracked us down by the roadside and commandeered Dad for an interview. Anton was our trusty translator, but judging from the often wry expression on his face, we wondered if he was toying with our responses or at a loose end to understand and translate our Aussie lingo.

The metropolis of Magadan was fast upon us with its visual stimulation of simple housing, Russian monuments and its haphazard vehicles and trucks. We now arrived at one of the biggest highlights of the trip, The Mask of Sorrow. This imposing monument on top of a hill overlooking Magadan pays homage to the prisoners of the Gulag system. The statue’s clearly evident teardrops are a painful reminder of deep, ongoing weeping as Russians confront and move on from this terrible past. It was a very solemn moment for us comrades. Each of us in our own way paid their final quiet respects to the Gulag inmates. We felt after riding this ‘Road of bones’ that some of the untold stories of these prisoners had slowly opened to us, and this statue was the final eulogy.

Though we were well and truly due for a bath, dipping our feet in the sea of Okhotsk was the next best thing. We had done it. Salt water never felt so good.

We let our hair down that night and celebrated at the house of our Russian friend Slava. The festivities centred on his homemade backyard banya (sauna). Imagine scantily clad men jumping between the hot sauna and the icy backyard pool, all while feasting on seafood with vodka to wash it all down. We weren’t just washing down the food but also laying to rest the whole memorable experience. ‘Peidodnya!’

The concluding Russian flourish was a final sighting of a bear while driving the back streets home, all within three hundred metres of five Aussies obliviously lounging in a pool! No one mentioned bears in the city, but somehow we were not surprised. This is a land that you have to experience firsthand, and no guidebook or even local advice can fully anticipate the rich breadth of experience.

Ro Privett has also developed an inspiring smartphone Outdoor Education APP ideal for outdoor programs. Please visit www.wildexposure.com.au/outdoor-ed-appbag-of-tricks

Ride On content is editorially independent, but is supported financially by members of Bicycle Network. If you enjoy our articles and want to support the future publication of high-quality content, please consider helping out by becoming a member.

Loved ‘living’ this epic ride whilst reading the delightful article. I wonder what the next adventure will be. Thanks for sharing a part of Russia that we rarely hear about.

Thanks Kerstin!

Glad you liked it…

next adventure? hah – something in Tassie – a little closer to home. You been to Russia? whats your next adventure?

Ro 🙂