Paid to ride?

Active travel makes a healthier society and a stronger economy. Simon Vincett looks at subsidising transport that’s good for Australia.

Damien Cook rides his bike four days a week, passing the thousands of cars lining Melbourne’s Eastern Freeway on his journey to and from work. His ride offers many benefits—reducing stress, improving his health, including his heart health—and being able to be social and chat to other riders. And while there may be some financial benefits from saving on fuel costs and parking, there are no tax incentives to keep Damien on his bike. He receives no tax rebates for his mode of transport—unlike those who drive company cars.

When asked if he’d like a tax break for riding his bike, Damien laughs, “Yeah, of course. They do it in Britain, don’t they?” But he’s modest: “In one way you think it’s a reasonable thing—it’ll get more people riding a bike. But then is it only riding to work or is it also riding for pleasure? It depends how it would work.”

The same sort of reasonable-person test applied to company cars throws up similar questions. In July, the Labor (Federal) Government estimated that 320,000 Australians used their company car wholly or mainly for private purposes. As a result, a new regulation was introduced and the FBT was applied to 100% of the benefit, except for strictly work-related driving that must be recorded in a log book for submission. This approximately doubles the amount of tax payable for the average user and effectively negates the benefit. As a result, leasing companies suspended activity and orders for cars, anticipating interest to dry up.

Tony Abbott has vowed to reverse company car restrictions, saying so with an Open Letter to the Australian Car Industry, Employers and Employees just prior to the September 2013 federal election. The letters states that the Coalition “wants confidence to return to Australia’s car sector” and claims “tens of thousands of people affected directly and indirectly” by the restriction of the company car benefit.

The question is: which is the best investment for Australia?

Car travel in Australia is subsidised in ways including low-taxed petrol and via tax breaks for salary-packaged company cars. It can be argued that these are subsidies helping to prop up a sedentary lifestyle and leading Australians down an unhealthy road.

For riders like Damien, a tax incentive for bike riding is a financial bonus. For Government, it could be one of the answers for a growing health problem.

Statistics show 57% of Australians aren’t doing the required amount of physical activity every day leading to a raft of health problems, including heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, depression and some forms of cancer. Such health issues add more than $1 billion to hospital and other related medical costs Government covers every year. It makes perfect sense then, that the Government should offer tax subsidies to bike riders.

Salary packaged company cars with no restriction on personal use offer drivers a tax saving of about $3,000 a year on average, according to the companies providing the novated-leases on the cars. These savings comprise a reduction in taxable income and avoidance of GST on the purchase of the car, on petrol and on maintenance. Costs of the car are deducted by the employer out of the pre-tax income of the employee, creating a Fringe Benefit. This attracts Fringe Benefit Tax (FBT) but only on 20% of the value because it is assumed that 80% of the use of the vehicle is for work purposes.

In limiting company car use to actual work transport, the Federal Government in July estimated to save $1.8 billion in subsidised personal driving. Some experts argue that drawbacks include state governments missing out on an estimated $100 million in stamp-duty revenue from new-car sales and about $50 million in registration fees each year. However, the overall savings to the Australian economy are clearly compelling.

Novated-lease providers and associated services certainly welcome a return the way things were but the Australian car manufacturing industry knows it doesn’t do much for their woes. When the system started in 1986 most cars leased or bought as a company car were Australian made but as tariffs were relaxed and foreign cars were available to Australians they have become a considerable proportion of company cars as well. Academics point out that a more effective prop for local car manufacturing would be a direct subsidy.

In addition to the $1.8 billion saving in personal driving subsidy, the Australian economy also stands to save due to the economic benefit part and parcel of more people bike riding instead of driving. In 2011 a study for the Queensland Government calculated millions in aggregate savings (via decongesting roads, health benefits, environmental benefits and infrastructure savings) could be made.

It stated that: “1,000 bicycle riders per day will generate discounted benefits of around $15 million per kilometre over a 30-year appraisal period ($1.43 per kilometre cycled, per person).” These are savings for a typical off-road path in an inner urban area.

If some of those who lost the benefit of driving the company car to work started to ride instead we can calculate the benefit. Currently, 1.5% of Australian trips to work are by bike. The government estimated that 320,000 people would lose the benefit of a company car for personal transport. If 1.5% took up riding instead, that’s 4,800 more active people. If they commuted 4km (to a train station, for instance) and the reverse home, that’s an economic benefit of $54,912 per round-trip commute by bike or $13,178,880 per year.

The greatest part of these savings is in health costs. A draft report from the federal Department of Infrastructure and Transport, Walking, Riding and Access to Public Transport, states “A typical cost benefit analysis for an active transport project shows that public health accounts for most of the economic benefits…The net health benefit (adjusted for injury) for each kilometre cycled is 75 cents.” For those 4,800 newly active commuters their 8km ride represents a $28,800 net health benefit per daily bike commute or $6,912,000 per year.

These economic savings increase with each further person who begins to ride and with each extra kilometre they ride as their fitness improves and the appeal and utility of bike riding becomes more apparent to them.

For people like Damien these overall costs savings to health are not part of the consideration to ride to work, however, the benefit to personal health definitely is.

“Basically I enjoy it and it keeps me fit—a sound mind and a sound body. I’d been suffering from a bit of anxiety,” he says. “It’s the best part of the day actually.”

A study by Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, published by the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, looked at 822 commuters from Adelaide over a four year period, some of whom always drove, and other who drove less, or very rarely. The car commuters gained between 1.3 and 2.4 kilograms in weight over the study period. Even those drivers who exercised during leisure time gained weight. In comparison, those that did not commute by car, and did sufficient exercise, did not gain weight.

Tax breaks for bike riding

In Australia the novated-lease company car system, taxed via FBT, is attractive to employees and employers alike for the financial benefits it offers both. There are obvious flow-on benefits to car manufacturers and lease providers. The system means an employee gets a reduced taxable income, avoids GST on the purchase and running of the vehicle and can potentially access discounts available through the bulk buying of their employer. The employer benefits by being able to offer a salary package worthwhile to the employee where the novated-lease element incurs a lesser cost to the business.

While in Australia no tax subsidies are provided for bike riders, there are other countries which do offer them. Belgium and the Netherlands offer substantial benefits while small ones are offered in the USA. Those notable schemes of the bike-filled European countries provide tax-free bikes to employees, but not through a complicated novated-lease system. They also provide generous payments to employees for the amount of riding they do (up to a limit). The differing success of the systems can be understood quite simply by investigating the amount of benefit offered to the employee and the complexity of administering the benefit for employers.

If such a system was introduced here, a bike tax-benefit system would have to recognise a key difference from the existing company car system: that the bike provided should be designated as being for personal use, primarily as a means of transport to work. So rather than a ‘company bike’, with the implication that it is for company use, it would be a salary packaged bike for personal use. In successful European programs, and in the moderately successful UK “Cycle to Work” scheme, the bike is linked to riding to work by an incentive paid to the employee for each day of riding to work. The purpose of these policies is the promotion of active transport, with all the societal benefit of better health, reduced pollution and congestion that that brings.

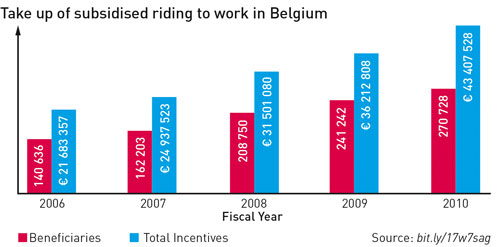

The exemplary scheme is in Belgium, where over 270,000 people—over 6% of the working population—have their ride to work subsidised by the tax system. The employer receives a tax refund for the payment of an incentive for employees who ride to work. The incentive is €0.21 (AUD$0.30) per kilometre ridden, limited to €3.15 (AUD$4.56) per day (€0.21 x 15km round-trip commute). For a person who commutes the full 15km daily round-trip and who works 211 days a year the incentive is limited to €664.65 per year (€0.21 x 15km x 211 days), which is AUD$960. In 2010, the average incentive was €160.30 a year per participating employee (AUD$232.11). Companies are also able to offer their employees a tax-free salary package of a bike, its maintenance costs and parking costs. This simple system is appealing to employees and is easy to administer for employers. In five years of operation 2006–2010 the number of employees taking up the scheme rose from 140,636 to 270,728—from 3.2% of the working population to 6.1%.

The Netherlands has a similar incentive, though the benefit is €0.18 per kilometre ridden (AUD$0.26). Employers are also allowed to provide employees with a new bike, but only once every three years. The value of this bicycle is treated as income, but if it is used for commuting, the value of the bike is fixed at €68 (AUD$98) for tax purposes. This applies to bikes up to a maximum value of €749 (AUD$1,085). Employers may also provide bike accessories, such as clothing, lights, locks and maintenance, tax free up to a value of €250 (AUD$362).

In Italy a subsidy took the form of reduced retail price for bikes. In 2009 subsidies of between €180 (AUD$260) and €1,300 (AUD$1,880) were provided on the retail prices of new bicycles, e-bikes and pedelecs.

In the countries Australia most often looks to for example, the USA and UK, there are also tax incentives for bike riding that have been developed after these European models.

The UK allows employers to pay employees up to £0.20 per miles ridden (AUD$0.34) and provide a tax-free bike. Unlike the European systems, through the Cycle to Work scheme in Britain the bikes are provided via a hire agreement, where the bike remains the property of the employer. The bike and accessories must total £1,000 (AUD$1680) or less including tax. The purpose is, the Cyclescheme website states, that “employees should use the bike mainly for commuting to and, if relevant, between work places.”

“Typical savings for employees are between 32% for basic rate taxpayers and 42% for high rate taxpayers, but the actual amount depends on the employee’s personal tax band and the way the employer runs their scheme. If the employer uses external finance to buy the bikes, then savings will be approximately 5% lower. Employers can typically save 13.8% of the total value of salary sacrifice, due to reductions in Employers’ National Insurance Contributions (NICs) due.”

In the US the employer does not have scope to offer a tax-free bike or accessories but “may provide a reimbursement of up to $20 per month for reasonable expenses incurred by the employee in conjunction with their commute to work by bike. The reimbursement is a fringe benefit paid by the employer the employee does not get taxed on the amount of the reimbursement.”

So what should we have in Australia?

Bicycle Network in 2009 proposed a tax incentive for bike riding, consisting of a tax-free bikes and accessories every two years for people who ride to work and tax breaks for employers for retrofitting bike parking, showers and lockers. It suggested a salary sacrifice system for a $1,500 package of bicycle, equipment and services from independent bicycle dealers. It’s something the bike organisation is calling on the newly elected Government to implement.

Bicycle Network’s proposal was that the benefit was only claimable by people who proved they rode to work by the submission of an annual log book for 12 weeks of commuting. The journeys in each week must amount to at least 25 kilometres. This is “based on someone living 3–10km from work and riding 1–4 times a week. People who live near work may need to do other trips to top it up. We don’t want a total distance for the 12 weeks, such as 300km, as some people will go out and do it in one day.”

At the time, Bicycle Network said:

“We think it would be very exciting to have an online declaration registry in which people log their purchases and kilometres that the Tax Office allowed to be deemed to be the same as a log book. All personal information would be private but the electronic log could report on what people are buying, how much they are riding, how many kilometres are accumulating and then the benefits could be calculated and displayed: this many tonnes of carbon saved etc.”

In a guest post on the popular bike blog Cycling Tips, Brad Priest proposed Australia should follow the UK scheme, Cycle to Work, for its provision of a tax-free bike and accessories to encourage commuting. Writing in 2010, Priest suggested that the appropriate value of the bike should be “$2,000 or even $3,000AUD to cover the cost of most average purchase values. However it would equally be sensible to not cap the purchase value as a large percentage of bicycle prices are above these average values. Alternatively, for a higher purchase value, the employee could use the capped value towards the purchase and the salary sacrifice period could be extended for longer than a year as per a motor vehicle.” By Priest’s calculations “there is the potential to save up to 38% on your purchase”.

Both of these proposals operate in similar ways to the Australia’s existing salary sacrificing for cars, using FBT provide the tax concession framework. This similarity makes it easier for the tax office to incorporate bikes as an item eligible to be salary packaged.

A tax-free bike would be great of course but how about getting paid to ride each day as well, like those European schemes? For the rider there’s the obvious perk of being paid for your commute. The employer benefits from employees requiring fewer sick days and being happier and more alert at work. The national economy benefits from reduced public health spending and lower transport-related costs.

To achieve the desired outcome of the work-provided bike being used for riding to work, the European schemes have tried and tested paying for each kilometre commuted to work. Half a decade of data shows that Australia can also access the health benefits of people riding to work with a similar incentive in this country.

For Damien it’s his passion keeps him riding rather than any financial incentives—but how many more Australians would get on their bikes if it was offered? It’s a question well worth the new Liberal (Federal) Government’s pondering.

Give riding to work a try. Get started here.

Ride On content is editorially independent, but is supported financially by members of Bicycle Network. If you enjoy our articles and want to support the future publication of high-quality content, please consider helping out by becoming a member.

Reblogged this on BikeNCA.

Great well argued blog. I always feel frustrated as I don’t know how we can get this message across. Politics is about 3 years in the future not 30, especially with the new federal government, Blogs such as this preach to we the converted.

About 12 months ago the governments hired thugs in blue threatened me with a hefty helmet fine – i have been driving to work ever since then.

No thanks to being treated as second class so by this ignorant pack of hypocrites.

Shame on them for enforcing a published road rule (#256) designed to reduce your risk of acquired brain injury…

There is an online log book system already in place. It’s called Strava.

This is a brilliant idea, but to be honest, given the ridiculously foolish ‘cars vs bikes’ culture in this country, I could never see it happening, despite our pedalling Prime Minister.

Hard to see some politicians understanding the benefit of cycling, and for some, it’s hard to believe they even know what a bike lookes like.

Another way to create financial incentives for active transport is to create financial incentives for more compact land use. When homes, shops, schools and jobs are close together, people are more likely to walk and bike for both business and pleasure.

Unlike the traditional property tax that imposes the same tax rate on both land and buildings, some Australian cities tax privately-created building values at a lower rate. This makes buildings cheaper to construct, improve and maintain. The higher tax on publicly-created land values has two surprising consequences. First, it actually helps keep land prices down. This is accomplished, in part, by reducing the profits from land speculation, thereby reducing the speculative demand for land. Second, it encourages development of high-value sites. High-value sites tend to be infill sites near urban infrastructure amenities — and these are the very locations where we want development to occur to create places that encourage walking, biking and transit.

For more info, see “Using Value Capture to Finance Infrastructure and Encourage Compact Development” at

https://www.mwcog.org/uploads/committee-documents/k15fVl1f20080424150651.pdf

As one of the converted it is depressing that we need to be paid to ride a bike. We already have enough people wanting free ‘rides’ from the government. The labor government had the right idea on company cars but the application was too heavy handed. A graduated reduction of the tax benefits and sensible application of work related expenses would work. I would prefer any money going to better bike facilities that make people feel safe riding a bike. There is enormous scope for this in all of our cities.

Another approach is to ask whether paying people to ride is the best use of public money, or whether building more, safer bicycle lanes (especially in regional areas) would improve cycling rates and rider health and safety.