Aidan Kempster reveals a staggering swathe of riding in nature in the Great Forest on Melbourne’s doorstep.

I’ve been staring at the stars so long I can feel the arms of the Milky Way rotating around me. A breeze is whispering through the trees and I wriggle further into my sleeping bag. I am floating in my hammock among the mountain ash forests of Victoria’s central highlands, less than 100 kilometres from Melbourne. I caught the train out to Hurstbridge with my bike nearly a week ago and have been riding forest tracks self-supported ever since. My days are spent grinding up hills and laughing down them while my nights are spent dreaming. I am so grateful for two wheels and the humbling companionship of nature.

We all know Melbourne is one of the most liveable cities in the world. There’s great culture, top notch food and world class entertainment. There are exceptional sporting facilities, universities, hospitals and schools. It is of course no surprise that Melbourne is also expanding, both in population and in urban sprawl. A few years ago, locals, forest scientists and a variety of community and environmental organisations united in a vision to propose The Great Forest National Park on Melbourne’s north-eastern doorstep. By creating a combined reserve system, they hope to ensure the longevity and connectivity of our native forest ecosystems, secure our water supply, and address shortfalls associated with the current divided management system. I heard about the plan from some friends, and looking for a cheap bike holiday early in 2016 I decided I would go and explore the proposed park and share my adventure on social media.

I can hear what you’re saying: “What is this Great Forest National Park? Why can’t I find it printed on any maps?” The Great Forest National Park is a proposal to create a large reserve of native forest from Mt Disappointment at the western edge, southeast across the broad swathe encompassing the Kinglake Ranges, Yarra Ranges, Kurth Kiln and Bunyip State Park, further east to Mt Baw Baw and Walhalla, and north to Lake Eildon, Rubicon and Mt Robertson.

While some of these areas are protected, most are not. The mountain ash ecosystem, which is dominant across the entire central highlands region, is one of the world’s most carbon dense landscapes when mature but is currently listed as critically endangered due to the ongoing devastation of clear-fell logging and the high fire risk.

I see the Great Forest as a giant playground. There is something out there for everyone. There are alpine huts near Lake Mountain, old (and operating) gold mines around Woods Point, and caves in the vicinity of Bunyip. The diversity and majesty of the land is everywhere: secluded valleys, giant ferns, all kinds of tiny marsupials and crystal clear streams. There are countless unnamed tracks that’ll take you on mystery adventures and what’s better, it’s so close to the city that five metropolitan train lines (South Morang, Hurstbridge, Lilydale, Belgrave and Pakenham) can connect you to different parts of the forest from the Melbourne side with relative ease. The clear advantage of this is that overnight routes don’t need to retrace steps, it is easier to get a large group together, and rescue in case of emergency is pretty straightforward. You don’t need to book a plane ticket, you don’t need to take time off work and it’s perfect for training and/or gear trials.

I started my touring adventure fundraising for the grassroots non-profit environmental organisation BeardsOn, using my beard as a tool to start conversations about conservation. I enjoyed this quite a bit, but I didn’t really run into a lot of people in the places I was spending my time. Most of the conversations I had were with people I took with me, and those experiences are some of the most valuable of all. To date (writing in September 2016) I have taken a dozen different trips into the Great Forest. By Christmas I expect to have completed another half a dozen rides or more.

My most recent trip to the forest was one of the nicest. My good friend James and I managed to pack the Norco Bigfoot and a Specialized hybrid into a hatchback sedan with a full complement of camping supplies for a trip out to Big River. We picked up a take-away pizza on the way through Healesville and dove pretty well straight into the tent once camp was pitched. We woke up early to finish off the pizzas and drink some coffee before hitting the road.

It was my first time out with the Bigfoot and like with any fresh ride I was trying to balance my desire to thrash it against making sure I didn’t prematurely bend it around a tree. We rode a 30km loop, including a decent section of hike-a-bike up one of the old Reefton logging roads.

It took us a couple of solid hours to go not very far at all, a phenomenon I’m becoming quite accustomed too.

When we reached the first ridgeline and got a nice bit of flat, I fired up the stove for another coffee and we snacked on muesli bars. Everything was going sweet, but I could tell this was going to be a real test of endurance for James, who hadn’t ridden his bike more than 5km in the last year and that was about the distance of the uphill part of this route! We reached the top mid-afternoon, just as the day was about to start cooling down. I congratulated James on his effort and after another snack it was time to enjoy the inevitable pay-off from such a gruelling endeavour.

I have developed a real knack for reading Rooftop Maps and my choice of road for the descent was spot on. Gum Tops was a delight. The next 15km took 45 minutes, never getting too steep or too rough, and James easily kept pace on his rigid hybrid with tyres less than a third the width of my own. The more agile bike might have some advantages for speed but the sheer sideways cornering ability of the fat bike made for what felt like a more natural free-flowing descent. If we had ridden the loop in reverse we would have been able to ride up this hill without too many problems, but going down the way we’d come up would have been extremely difficult, particularly for James’ bike. The gradual descent of Gum Tops was a strong reminder of what I love most about forest riding. A couple of times I found myself ploughing through torn up corrugations and into piles of sticks I’d normally avoid like lava but the Bigfoot charged on at full pelt like they were part of my imagination. At the bottom of the hill we found the graded gravel Eildon–Warburton Road and followed it back to Big River.

We made it back to camp just on nightfall. I was grinning from ear to ear and James all but collapsed with a pained smile on his face muttering something about how it was the hardest thing he’d ever done. I cooked up a feast of roo burgers and sausages and we ate while gulping down Mojito flavoured electrolytes and reliving the day’s events. The next day we took it easy, I spent a few hours playing around trying to learn some mountain biking techniques and James enjoyed a parallel activity with his camera (you’ll find his handiwork accompanying this article). We were back in the big smoke before dark the same day, I was brimming with excitement for the next trip and James was pleased to have come, but was planning to do a bit more training before he heads back out.

We made it back to camp just on nightfall. I was grinning from ear to ear and James all but collapsed with a pained smile on his face muttering something about how it was the hardest thing he’d ever done. I cooked up a feast of roo burgers and sausages and we ate while gulping down Mojito flavoured electrolytes and reliving the day’s events. The next day we took it easy, I spent a few hours playing around trying to learn some mountain biking techniques and James enjoyed a parallel activity with his camera (you’ll find his handiwork accompanying this article). We were back in the big smoke before dark the same day, I was brimming with excitement for the next trip and James was pleased to have come, but was planning to do a bit more training before he heads back out.

Every track that’s ever been built for a 4WD can be tackled by a cross country mountain or cyclocross bike with the occasional hike-a-bike steep sections. For short stints even 23mm tyres would do the job, so hybrids and commuters are going to be fine if you avoid potholes. The trails are so wide you can choose from a variety of lines – you don’t need any previous mountain biking experience.

Mostly the trails are compacted clay or dirt, scattered with loose sticks, leaves and rocks. On major access routes you’ll find quite a bit of gravel, usually well graded and reasonably fine. The worst surface is super chunky gravel, which is only laid in particularly loose areas with high or heavy traffic, and thankfully there’s only ever short sections of it.

It’s always better to get off and walk up the steepest sections than try to grind over the lowest gear with all your weight. Many riders I have ridden with push the limits of their anaerobic capacity way too early. I say leave the uphill sprints to the Tour de France. Some less-used forest tracks can be extremely steep, slippery, dotted with rocks and plagued by ruts. These can be a lot of fun too, though in rain and extreme heat, it is worth remembering that none of the tracks were built or are maintained as bike trails. What berms, jumps, roots and switchbacks you find are freeform, and though you can easily spend hours or days without seeing another person, there could always be a car or horse around the next blind turn.

When I started my effort to explore the proposed Great Forest, I had no idea how much history there is scattered underneath the canopy. Italian prisoners of war from the North Africa campaign were kept at Mt Disappointment in labour camps. At Kurth Kiln there was a six-metre tall furnace to generate charcoal for powering cars, which you can still see today. In 1864, shortly following the discovery of gold, there were 36 hotels in Woods Point; now there’s only one. In the Rubicon’s aptly named historic area, you’ll find suspended tramways through the forest (remnants of the former timber harvesting operation), and a scheme of hydroelectric power stations (although these are still active and access is prohibited).

When I started my effort to explore the proposed Great Forest, I had no idea how much history there is scattered underneath the canopy. Italian prisoners of war from the North Africa campaign were kept at Mt Disappointment in labour camps. At Kurth Kiln there was a six-metre tall furnace to generate charcoal for powering cars, which you can still see today. In 1864, shortly following the discovery of gold, there were 36 hotels in Woods Point; now there’s only one. In the Rubicon’s aptly named historic area, you’ll find suspended tramways through the forest (remnants of the former timber harvesting operation), and a scheme of hydroelectric power stations (although these are still active and access is prohibited).

In Toolangi and the Ada block you can walk right up to massive, ancient trees that give you an incredible appreciation for what these forests would have looked like a few hundred years ago, and what they could look like a few hundred years from today. Around Marysville you can see the sickly white trunks, totally petrified by the ferocity and havoc of the Black Saturday wildfires.

There is a lot waiting to be explored in the Great Forest. It is truly is Melbourne’s next great attraction.

To keep up to date with my forest adventures, follow me on Facebook.

The gear to make it possible

It is important to be prepared with any adventure into nature. Even if you are just doing a daytrip from a carpark or campground, make sure you know where you’re going, take enough food and water for the day and have a plan for what you’re going to do if something goes wrong. You should be prepared for sudden weather changes, flat tyres, exhaustion and dehydration. Mobile reception can be temperamental, though evidenced by my facebook account not unattainable (get onto the nearest ridge or climb a mountain), and there is a FireReady.gov app that can give you real time information on fires.

A handheld GPS allows me to predesign routes as ‘breadcrumbs’ from a computer screen and follow them without having to fumble through different maps and use a compass. However, I would always recommend bringing a paper map and compass. The Rooftop Maps have been instrumental in getting me this far and I will continue to take them with me, even when I have a GPS.

As a young person concerned about sustainable transportation and travel, I look at bike touring as the ultimate way to have fun, keep fit, see exciting places and meet interesting people while minimising my carbon footprint. Modern technology has decreased the weight of bikes and camping gear, while at the same time increased their strength, versatility and durability, so it is no wonder to me that bikepacking has emerged as a popular pursuit in recent years.

As a young person concerned about sustainable transportation and travel, I look at bike touring as the ultimate way to have fun, keep fit, see exciting places and meet interesting people while minimising my carbon footprint. Modern technology has decreased the weight of bikes and camping gear, while at the same time increased their strength, versatility and durability, so it is no wonder to me that bikepacking has emerged as a popular pursuit in recent years.

For overnight and longer tours it is vital to bring a warm and waterproof sleeping setup, even in summer. There is absolutely nothing worse than being unable to get comfortable and relax after a long ride. A waterproof bivvy bag replaces my tent/hammock, dropping overall weight and the time it takes me to setup my bed to about a minute, a few more if I am setting up a rain fly.

A strong LED light and a series of battery packs means I can ride all night if need be and, combined with the ease of my bed setup, it means I can make the most of the often spectacular hours of low-light without stressing about finding a place to set up camp.

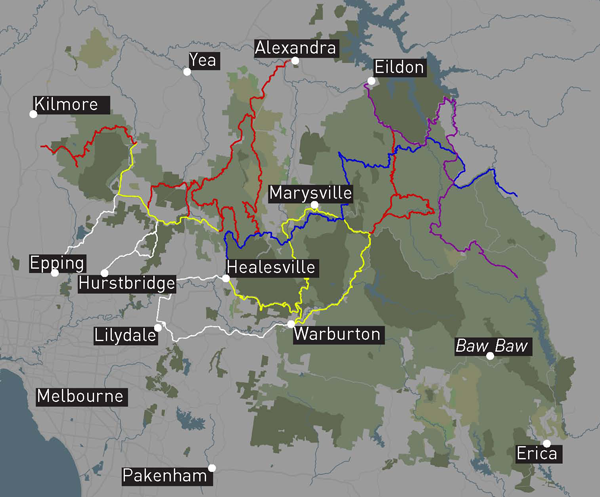

About the map

This map shows the easiest train to forest connections (in white). I have used and a combination of tracks within the Great Forest that I have ridden (in red), scouted or plan to tackle (blue and purple) in the future. There are also a few major roads shown (in yellow) that are popular with road bikes. As you can see these tracks form a network, so you can choose your own adventure as I have been.

These routes are by no means exhaustive of the forest tracks that exist in the region either, there are hundreds of other adventures you could plan for yourself and more I have done that would make this image even more difficult to read. The Bicentennial National Trail (marked on this map in blue) and the Lilydale–Warburton Rail Trail (white) are part of the network I have used.

All of these routes are downloadable from my website, from which you’ll be able to interact with the map, turn layers on and off, as well as see and download any or all of the routes you are interested in. The data I have been working from is all freely available, but unfortunately incomplete so some of the files I have recorded by hand in the forest traverse tracks you won’t find on Google or Open Street Maps.

If you want to browse these online, the Victorian Government provides a very workable resource called Forest Explorer, although I have not found a way to use this data meaningfully offline. If you don’t own your own specialised GPS unit you’re in luck, as the GPX files available on my blog can be followed by many smartphone apps like Locus or OruxMaps.

Photography by James Fong

Photography by James Fong

Ride On content is editorially independent, but is supported financially by members of Bicycle Network. If you enjoy our articles and want to support the future publication of high-quality content, please consider helping out by becoming a member.