Liveable speeds

Across Australia authorities are reducing speed limits to 40km/h in residential streets, school zones and in shopping thoroughfares. But should they be lower? Simon Vincett investigates.

On the outskirts of Melbourne is the gorgeous coastal area of the Mornington Peninsula, a boot-shaped municipality of rolling land separating Port Phillip and Western Port bays.

Ocean views are mixed with open land for wineries, spas, golf courses and tourist attractions and, of course, the tighter-knit residential areas.

The population of more than 150,000 people uses local roads to ride bikes, walk or drive around town. So do the visiting tourists.

While it’s a wonderful place for a holiday, there have been problems with traffic on local roads. Prior to 2012, suburbs including Rosebud had “an alarming” number of pedestrians and bike riders involved in casualty crashes in residential areas and on local rural roads.

It led to the Mornington Safer Speeds project, supported by funding from the Victorian Traffic Accident Commission and VicRoads, including speed-reduction trials being established in the area.

Doug Bradbrook is a Traffic & Road Safety Strategist with Mornington Peninsula Shire and has recently overseen the assessment of the trials, which began in March 2012.

The trials were on two different types of streets, local roads in the residential area of the town of Rosebud, where the speed limit was reduced from 50km/h to 40km/h, and on rural roads, where the limits were reduced from 100km/h to 90km/h on some roads and from 90km/h to 80km/h on some other roads.

Despite a great number of local residents driving to work (more than 47,000 of the 150, 777 people drive to work according to Mornington Peninsula Shire’s community profile) the local community has embraced the speed reductions.

“In essence, community support is 80%,” Bradbrook reports, based on surveying Mornington residents before and after the trials. “It’s higher in rural areas, where 90% of people are in support of the moves.”

The council promoted, and residents now support, that “research indicating reducing speed limits by just 10km/h results in a significant reduction of serious and fatal crashes.”

It wasn’t just the attraction of fewer serious or fatal crashes that received support from local residents, it was also the fact they identified that slower speeds would mean more people walking, more kids and adults riding bikes in the neighbourhood and a closer community as a result.

“Across all groups the main reason for this support was that further reduced speed limits were thought to be more appropriate for children and the elderly,” Bradbrook said.

This perception of improved amenity from lighter traffic was first measured and confirmed by Donald Appleyard in his 1981 book Livable Streets. Appleyard, a professor of urban design, compared three residential streets in San Francisco that were very similar except that one experienced heavy amounts of traffic, one had medium traffic and the one had few vehicles using the street. It was his findings of variation in community connectivity that broke new ground. It showed there was another measure of the impact of traffic on human health, apart from the raw numbers of fatalities and serious injuries.

His studies found that residents of the street with low car traffic volume had three times more friends than those living on the street with high car traffic. A lightly trafficked street could contain neighbours that were close but a heavily trafficked street kept neighbours apart.

People stop cycling, and walking, to local destinations, such as local shops, schools and friends, as they do not feel safe or comfortable doing so

The other significant thing Appleyard identified was the extent of the home territory or neighbourhood that residents felt they belong to. In streets with heavy traffic, most people nominated that their neighbourhood was their apartment and not much more, often not even the rest of their building. These people said that theirs was not a friendly street, offering responses such as “No one offers to help each other”. On streets with little traffic, people felt their neighbourhood included multiple families in the street and the area extended for the length of their block on both sides of the street. An example response was “People are warm on this street. I don’t feel alone.”

These insights underpin the assertion from Bicycle Network that “Unless provision is made for quiet streets in residential areas, bike riding will remain an underutilised activity and transport.” The organisation points out while nearly all bike trips start on local residential streets, “the speed and volume of most local street do not suit most potential bike riders, especially children and family groups, as there are too many motor vehicles traveling too fast”.

The organisation is now running a campaign to convince state and local governments to move to 30km/h in selected local streets and precincts.

Its argument is that slower speeds in local streets mean more people will be happy to ride their bikes and walk, the flow on effect being that local suburbs will be healthier as people become more physically active, and socially active.

Bart Sbeghen, who coordinates the Healthy New Suburbs program for Bicycle Network, explains the link between high-speed traffic, reduced community and reduced bike riding.

“People stop cycling, and walking, to local destinations, such as local shops, schools and friends, as they do not feel safe or comfortable doing so,” says Sbeghen. “People also stop cycling and walking to other destinations as they do not have safe routes to get to surrounding areas.”

Sbeghen traces the roll-on effect, “Less confident people, including older people and children, stop riding and walking leaving only the more confident adults, leading to less diverse public spaces. People lose contact with their neighbours and make fewer friends.”

“All the above lead to less people using their public spaces and streets, which make them less welcoming to those who continue to use them. People feel less safe when alone, especially at night.”

Dr Alison Carver, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Centre for Physical Activity and Nutrition Research at Deakin University, has measured how lower speeds effect resident’s perception of liveability and specifically the scope for bike riding.

Her questions posed a theoretical reduction of speeds in residential streets to 30km/h, a speed that her research has shown is the best maximum for a liveable street.

“I found that 42 per cent of local residents (in inner Melbourne) said they would approve of 30km/h,” reports Carver. “I asked them about how they thought their behaviour would change regarding walking cycling and social interaction,” Dr Carver said.

“People were positive that they would walk and cycle more but the strongest findings were how they thought the behaviour of children would change.

“I found that 47 per cent of respondents agreed that more children would walk and cycle in their neighbourhood and 44 per cent agreed that more children would walk or cycle to school,” she added.

“Almost a third thought there would be more interaction on the local streets,” Carver continues. “That’s really important for mental health purposes and for building social capital, with people getting to know their neighbours. It also combats the stranger danger issue. If people actually know who’s in their neighbourhood then there’s more of a collective responsibility of adults in general who are looking out for kids on the street.”

While organisations and researchers look at liveability and health as reasons to reduce speed in local streets, roads authorities look to reduce speeds based on the numbers of serious injury and death caused by motor vehicle crashes each year. Many studies have shown lower vehicle speeds lead to fewer crashes and/or less serious consequences as a result. For roads authorities, and governments, fewer crashes seem to be their ultimate goal. As the NSW Road Traffic Authority website states: “Extensive research has shown that even modest reductions in travel speed will result in substantial reductions in the incidence and severity of road crashes.”

Jan Garrard, a part-time lecturer at Deakin University’s School of Health, writing in 2008 for the Safe Speed Interest Group, identified this approach as an old, reactive way of thinking and predicted a move to a more beneficial, proactive approach. “Traditionally, little consideration has been given to the additional, non-injury benefits of speed reduction,” she stated.

“These are multiple and wide-ranging, and are likely to include increased active transport and the associated benefits of active living and reduced motor vehicle use. If these ‘externalities’ were included in algorithms used for setting speed limits, it is likely that the benefits of speed reduction in urban areas would outweigh the disadvantages in the form of small increases in vehicular travel time and associated costs.”

Change in vehicular travel times was an aspect of the Mornington trial assessment, as a significant aspect to consider. However, it turned out not to be significant. While actual speeds in the residential streets did decrease following the reduction of the signed speed limit, travel times did not significantly change.

“Monash University Accident Research Centre found that there was no real impact on travel time,” says Bradbrook.

This is similar to the experience of the City of Melbourne, who also anticipated there would be no significant change in travel times following their introduction in late 2012 of a 40km/h limit on all streets within the central grid.

City of Melbourne is one of several leading proponents of speed reduction on local streets around Australia—other inner-city councils, such as Yarra and Port Phillip, have also led the charge. Yarra has 100 per cent of their local roads at 40km/h and has indicated that they would like to reduce speeds further to 30km/h.

Doug Bradbrook is pleased not only because Mornington is pioneering having reduced speed limits in Melbourne’s outer suburbs, but also because the trials are showing some great success.

The results are similar to those predicted by an independent transport consultancy.

“They found that overall, the safety benefits are expected to be positive,” says Bradbrook. “They predicted reductions in fatal crashes of 11 per cent in residential areas, 7 per cent on rural 80 km/h roads and 1.5 per cent on 90 km/h roads. Serious injury crashes are predicted to reduce in the range of 0.1 to 6 per cent across the residential and rural roads.”

For a convenient overview of Donald Appleyard’s Livable Streets research see Streetfilms 2010 film Fixing the great mistake.

Ride On content is editorially independent, but is supported financially by members of Bicycle Network. If you enjoy our articles and want to support the future publication of high-quality content, please consider helping out by becoming a member.

Reblogged this on BikeNCA.

Councils have to bite the bullet, get serious about this, and have car-free zones like many European villages.

We have pushed speeds down as low as we can without re-architecting streets. If the road is a highway cars will speed down it. If the road is narrow, winding, with humps at frequent pedestrian crossings and a physically separate bike way, then (and only then) will cars get the message and accidents become less frequent and much less severe.

30 kph for residential streets strikes me as quite difficult to enforce, as cyclists would also be limited to this speed. There are already lots of drivers who cannot stick to 40/50/60 kph in residential streets, how low does the limit really need to be?

Typical councils. Easier to lower speed limits to unreasonable levels rather than make streets wider with separate large footpaths and cycle ways so all can be accommodated. Also separate Freight roads as in the old stock route days to get the big trucks off the road- has anyone commented on the fact the trucks on the local road now are 3 times the size of those in 1980?? It takes more petrol to keep to the low speeds so more petrol tax for government and more frustrated drivers angry at difficult road sharing. One way streets as in Europe and cities, Car free shopping localities, adequate off street parking are all better ways to go but ….. it all comes down to $$$$. Rates and Rego money going elsewhere so can only afford new speed signs. Instead of a them and us mentality bikes and pedestrians and drivers should be demanding better roads. Taking us back to the 18th century is not the way to go. We have the numbers if we join the walkers and drivers and riders together.

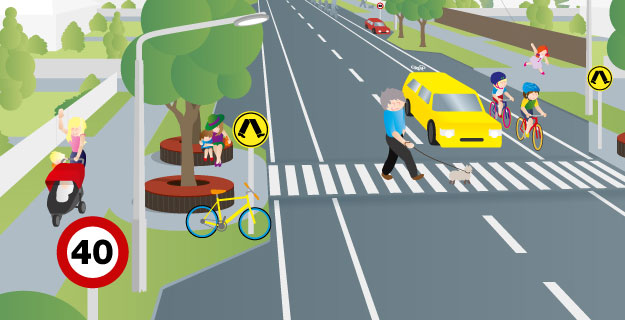

My case is strengthened by the picture in this article. Bike paths, Foot paths, crossings, road ways. All councils should be made to create an environment like the picture in all new areas and should be redesigning older areas where practical. LIvable means areas for everyone – including cars.

Don’t push too hard to treat the whole city like a pedestrian crossing. Drivers have a right to a reasonable expectation that if the road can be driven safely at 50 km/h at some times, then those rights will not be taken away by a minority who push to have the limit lowered at all times. 40 as a blanket rule is too slow, 30 is ridiculous. Yes, I do ride on the roads and there are obligations on all of us.

Did you understand the article, it is about livability, and BTW cars (drivers) do not have rights – people do.

Cars, bikes, walkers, all have the rights of the people using them.

It goes without saying that the more vehicular traffic is slowed down, the fewer the accidents and the less the injuries will be. Bicycles traveling at 25 Kph can be dangerous too. If we drop traffic speed to walking pace, we’ll all be saved. The argument is essentially reductio ad absurdum.

I agree with Michael that beyond a certain point, traffic speed has to become a function of road architecture. Arbitrary reductions in speed limits will likely produce limited compliance, which itself is dangerous.

In recent years Vic Roads has decreased speed limits, and extended their zoned areas and hours of operation around road works, even when no one is working there. They are widely ignored.because motorists think that some health and safety bureaucrat is having a lend of them to keep themselves busy and justify their existence.

Communities have to enter into a local dialog with motorized traffic which isn’t just rules but function based. Programmable electronic signage could be turned on and off to allow for community street use as needed, for clearly defined non traffic uses, which are communicated to motorists. Or they automatically go on when children are going to and from school, and appropriate messages are communicated to motorists to that effect.

Effectively communicating changed traffic parameters, either through permanent street design or appropriate signage that flags temporary street use change will get the compliance from motorists because they can see why they need to change their ordinary behavior.

Forcing drivers to reduce their speed to 30 or 40 kph and drop into second or third gear without obvious cues, is an invitation to ordinarily law abiding people to break the law. and regard it as an ass.

As a resident of outer suburban Melbourne who relies on a car for transport (as well as public transport, cycling and walking) I still don’t see the need for road transportation to take precedence over creating safe neighbourhoods for ourselves and our children. We should be prioritising the safety of the most vulnerable. Pedestrians first. Cyclists second. Motor vehicles third. If we were to go as far as to zone all residential streets and activity centres as shared roads, requiring motor vehicles and cyclists to give way to pedestrians, and reducing speed limits accordingly, it would not unduly impede my movement however it would create safe, peaceful and welcoming neighbourhoods. Kids should be free to play cricket on the road. Learner cyclists should be free to wobble their cruisers down the street. Daydreaming teenagers and tipsy wage slaves walking home from the train should be free to stumble erratically across the road. The blind, the disabled, the elderly and the young shouldn’t have to fear for their life every time they want to cross the road. People need to slow down. A lot. This is not Mad Max and you are not the toe cutter.

What rubbish. Your idea would be to return to the 18th century. Maybe we should bring back horses too. And the man with a lantern to walk in front of cars to warn people (who aren’t paying attention) that there is a car on the “road” – not the footpath…. Pedestrians need crossings and bikes need bike paths and cars need roads. Accommodate all – we are in the 21st century so progress is needed not retro action Most local shopping precincts – like the Mornington peninsula in the article should be car free zones with adequate off street parking areas. Share the world – don’t cut one group out. I am disabled and cannot walk far so need the car to get around as I still like to travel to these places No cars means isolation as in the 18th century when most people did not leave their villages –

In urban America, land of the car, drivers stop to let pedestrians cross the road mid street in residential areas, and drive at a slow speed that allowed them to do so. People I spoke to about this were often unsure whether or not they legally had to stop; they just stopped out of common courtesy. “I’m driving thru someone’s neighborhood of course I’m going to stop”. Highway speeds were higher than here, with all the carnage resulting from that.

In regional victoria I find that locals often drive well below the speed limit in town, give way to pedestrians at roundabouts (when they legally don’t have to) and often mid street. Which is why the lowering of speed limits on the peninsula has been embraced.

In hometown Melbourne the give way to pedestrian laws that we have are routinely ignored by many (at side streets, drive ways, slip ways and shared roads) and out where I live driving anything less than 5 or 10 km over the speed limit is seen as obstructing traffic. And I’m talking about nice grey haired old ladies behind the wheel not teenagers in hotted up Nissans.

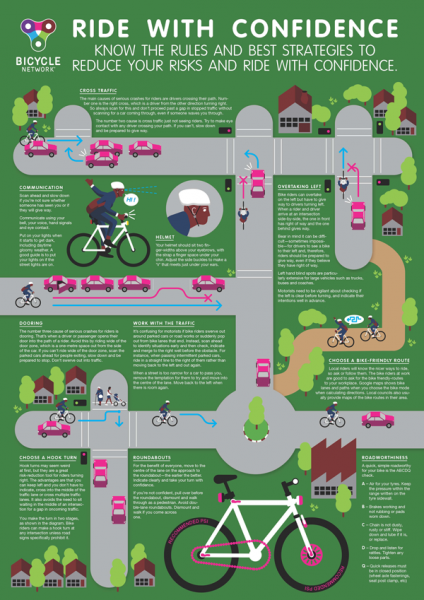

While I support the general thrust of livable streets it’s not clear to me whether the illustrations by Thomas Joynt showing door zone bike lanes are meant to be the BEFORE or AFTER pictures. They don’t seem too livable from a cycling perspective.

Something is missing from this road speed message. For those of us that walk a lot in our suburban area we feel very forgotten by Vic Roads at every light controlled pedestrian crossing. We do need to slow traffic down but we also need to accept that pedestrians and young cyclists use crossings and for those that obey the signals and wait for ages, something needs to be changed. Why are pedestrians and young cyclists put last at light controlled crossings? Why do we have to wait so long to be acknowledged? Vic Roads signal designers need to review their rules and give all users a fair go.

30 k limits , bite me, I’d get booked every day riding to work. I might support a 40 k limit if all speed humps were removed. I’m not going to ride to the local shops to do my shopping , never ever, that is just stupid. The real problem is that there are way too many people out there that should not ride or drive. All those cyclist that go through the red lights in Chapel St. are not going to stop running lights because of a lower speed limit. Likewise all those motorist that drive in the bike lane. And what’s with the growing trend not to wear a helmet! Lower limits are not going to save those people.